[Arturo Herrera]

I think at this point it's clear that everybody understand that corruption is one of the most important problems in every country. It's pretty much at the top of the list in terms of the issues that citizens complain about, and pretty much at the top of the list in terms of the frustrations that citizens have. But while there's agreement on this issue, there's not a clear-cut agreement about the costs of corruption.

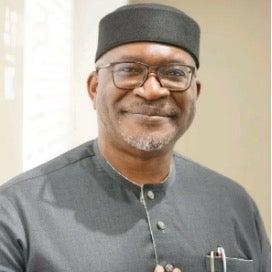

[Patrick Alley]

I think the first thing I'd like to say is that a lot of people don't really understand that corruption is far, far more than cash in a brown envelope. Corruption is not a victimless crime, and we all are victims of it.

[John Githongo]

Corruption does more than anything else to destroy the very essential relationships in society that are needed to have peaceful, harmonious development in a society. It undermines the very glue that holds society together, where cannot trust each other, and when you can't trust each other, even doing simple things becomes extremely difficult.

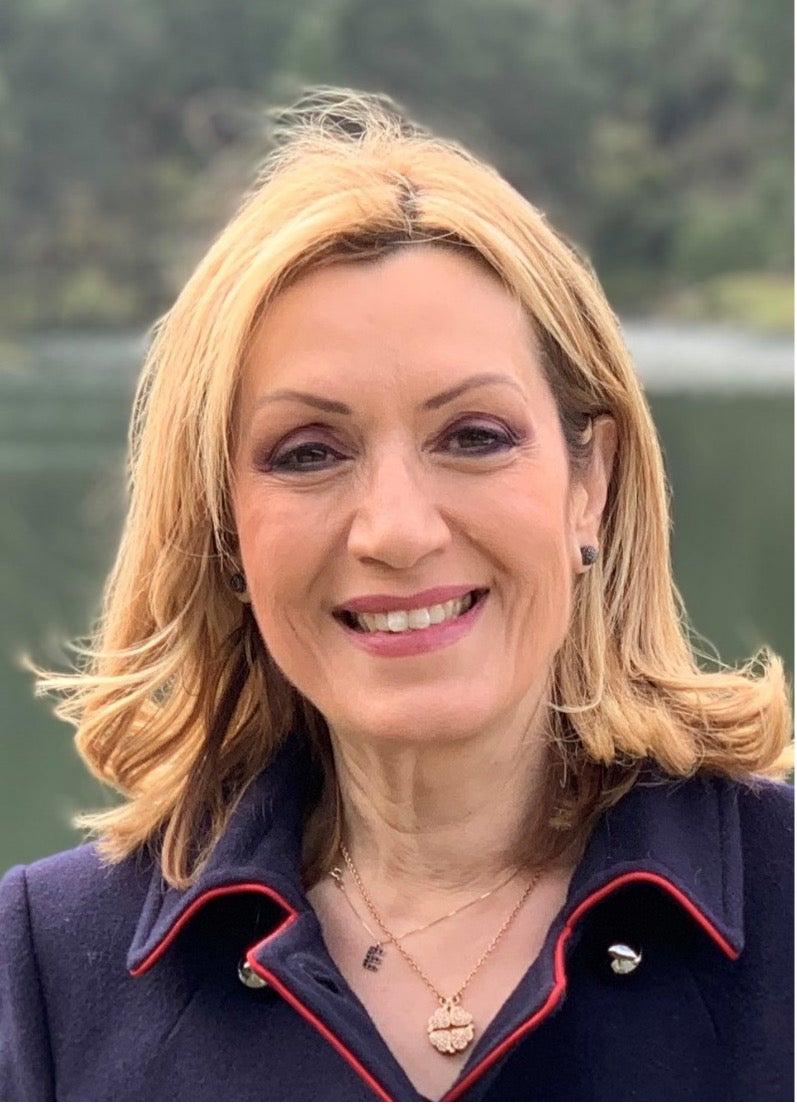

[Delia Ferreira]

The institutional costs of corruption are also important, and you cannot measure that in figures. You measure that in a successful future for a country, a future full of opportunities for people to work, study and live in freedom.

[Patrick Alley]

I think if you're looking at the destruction of the world's rainforests, the illegal fishing of the world's oceans, the wildlife trade, all of these things involve criminality and corruption, so virtually every environmental crime you see is a crime of corruption in its root.

[Delia Ferreira]

Corruption is, I would say, at the heart of our failures as society. You can think about, for instance, the fires at the Bangladeshi textile industry. Everything was okay, certifications were signed and given to the owners, but nothing was in place in case of fires, and the result was lots of people dead. That's a huge, huge cost. You can think about the Beirut blast for instance, with parts of the city completely destroyed, which is not only infrastructure. It was the apartments of people, and of course the very tragic thing of lives that were lost because of the blast. That's the cost of corruption, not the amount of the bribe paid for a certification without doing the proper controls. The cost is people's lives and people's possibilities. Corruption is a problem for all of us, all of the citizens, and we must all work to tackle corruption.

[John Githongo]

It's time for a reboot and I think that is underway, and it's being driven by the indignation and anger of young people.

[Arturo Herrera]

At the World Bank, we are, among other several things, working on three different parallel channels. One, we are obviously discussing how to strengthen institutions and how to strengthen trust in government. On the other hand, we are still working on the old-fashioned cost of corruption, and trying to fine tune the cost of corruption at the micro level, at the sectorial level. But we are really interested in trying to kick off a conversation about these other costs of corruption, the ones that imply and have costs in terms of the social contract, et cetera. This is pretty much a work in progress. This is kicking off an internal debate, quite interesting. People are passionate about it. We would like to invite you to join this conversation.

[audience applauds]

[Simon Fowler]

What an attention grabber. Good morning everyone, and good morning to everyone watching us on World Bank Group Live, which is a streaming platform going out across the globe in a number of different languages. My name is Simon. I'm going to be your master of ceremonies and host for the next two years. I'm a professional master of ceremonies, and I'm going to try to make sure that we do things properly for the next two days. That's what governance is about, correct? And governance told me to make sure we do that. So thank you to the governance team for having me here. I'm thrilled to be here, and we're going to kick off straight away by some opening remarks for this incredible forum, Anti-Corruption For Development with Roby Senderowitsch, the Practice Manager for Governance Global Practice. Roby, please.

[audience applauds]

[Roby Senderowitsch]

Good morning everyone. Thank you. And for those of you who came from far away, I know. Where is David from Solomon Islands? I met with him yesterday. It must be Tuesday for you already. Thank you so much for coming all the way here, all of you here. Just to do a quick check-in. This is a very important day for us, a very important crowd for us as well. Raise your hands if you are coming from government or public sector agencies, parliaments, justices, the judiciary, raise your hands. Thank you. Raise your hand if you are coming from civil society organizations, the academia think tanks. Thank you. Raise your hand if you are coming from the private sector, private sector companies, chambers, associations. Good. Raise your hand if you're coming from the media. We have a few, and there's a special session this afternoon about that. And if you're coming from other international development institutions as well [inaudible]. Thank you all for being here today. We are starting already on time and we are going to keep this for the rest of the two days. Simon said he's going to be with us for the next two years. Was that an expression of hope?

[Simon Fowler]

Hope.

[Roby Senderowitsch]

Yes. Thank you, Simon. And now I'll pass it to Arturo Herrera, who is our Global Director for Governance, so we can start this wonderful event. Thank you. Arturo.

[audience applauds]

[Arturo Herrera]

Thank you, Roby. I'm going to be very, very brief. They told me that my job today was to introduce Pablo, and that's a pretty concrete and a great responsibility, but let me just share a few thoughts before doing that. It's almost a year since I came to The Bank and I came with a responsibility with a very large portfolio. Everything from tax administration, budget efficiency, e-procurement, et cetera. As I have been traveling across the world, these topics keep popping up. But the one that is most consistent, the one I'm hearing everywhere I go, is the concern about corruption. Last week I was in Jamaica in the INTOSAI Meeting, which is a meeting that put together supreme audit institutions, and the main issue there is the agenda of anti-corruption. Two weeks ago, I was in Ivory Coast, in something called the Hunters Corruption Alliance, and the title speaks for itself. As I said, this is a topic that I keep hearing, but I keep hearing from completely different stakeholders. I hear it from people who come from the transparency and accountability agenda. I hear it from people in academia, which might have made a research program about trying to understand it. I hear it from people who think these issues need to be addressed from the angle of civil society and society participation. There's also the judicial angle. There's a very wide variety of opinions, and I think what this meeting over the last two days is about, it's actually about learning from each other. There's no one single silver bullet about how to mitigate the risk of corruption or about how to eliminate corruption, and this is what this conference is about. Now for my main job. As I said, as Roby mentioned, there are many institutions here, many institutions that care about anti-corruption and the World Bank is one of those institutions, and Pablo Saavedra, The EFI World Bank Vice President is going to address you, to kick off this meeting. Thank you. Pablo.

[audience applauds]

[Pablo Saavedra]

Good morning and welcome to this Anti-Corruption for Development Global Forum. I would like to start by thanking our co-hosts today, the Transparency International, UNODC, USAID, the United Kingdom's FCDO, the Foreign Ministry of the Netherlands, the Chandler Foundation, and the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Center. This is a work that we are all doing in common and this is a big agenda for all of us. Corruption continues to be a very critical issue for all of us here and in the world, and it carries very large costs for developing countries. Unfortunately, it has also a very disproportionate impact on the poorest and most vulnerable as you were seeing in the video, by increasing the cost of health, the cost of education, water, justice and even taxing transactions every time that citizens interact with government in some instances. It also affects public infrastructure, large projects that go into large overruns, costs that were not part of the original project. We run into issues of low quality in infrastructure, that then needs to be addressed by additional fiscal cost of doing renovation and refractions et cetera, at the cost of taxpayers and all citizens. And also infrastructure that has poor safety, and then we pay sometimes in human life those costs. Corruption also affects all that in public infrastructure. And of course, it reduces a private sector investment, because private sector investment wants certainty, wants rule of law and corruption doesn't bode well in that context. It also increases the financing cost of the sovereign, and by doing that, influences the cost of everybody in the country. Corruption cost permeates across different aspects. Actually, we were measuring these type of issues in our enterprise surveys. We do this in 144 countries. Just there, one in five of the respondents, these are firms, highlight that they had to make an informal payment for procurement. They admitted there. Procurement is one of those large categories of corruption that takes place in countries. Think about a developing country. On average, of course depending on the size, they spend between 3% and 8% of GDP in public procurement. Of course, larger economies spend more than that, but that's a significant chunk and there's significant corruption is one of the main avenues. Curtailing that, curving that has a big influence. Technology is giving us an opportunity now over the last few years to tackle several avenues for corruption. One is this issue of procurement, and e-procurement, making public purchases of goods and services of the government, brings transparency, reduces the incentives and gives the clarity that this process needs. By all means, it doesn't cut corruption in its totality, but it helps move us in the right direction. Same for taxes. At the beginning, it's costly to implement measures to have electronic invoicing and have a more digital approach to stop avoidance and especially evasion in taxes. But over time, firms get used to it. It's a much more transparent way to approach the issue, and citizens also appreciate that there's less interaction with tax officials in some countries where this is problematic. So that's another way. Another way that we are seeing a big surge including in projects in the World Bank, is through GovTech. GovTech offers an avenue to automatize and put in a digital way all the interactions that citizens and governments have with each other. By reducing that human interaction of citizens and government, we also reduce opportunities for corruption. Typically, we call those interactions between citizens or small firms and government petty corruption. But for those people, especially the ones that are poor, vulnerable, have low income or small micro firms, it's a big cost. It's a tax that they have to pay. Tax in money, tax in time, et cetera. Bringing that to the government interactions with citizens also is a very important avenue to build trust. That's one block, technology. But there's a second block that is well known and we see that it's also helping a lot, and it is access to information. Access to information puts forward the opportunity for journalists, NGOs and citizens to access the information that the government has on all categories, on all issues. That on its own helps to bring the demand side to this. This forum is about building trust, and to build trust, you need the supply side interventions, but also you need the demand side as aspects of better governance and anti-corruption, and that citizens engaged and looking at what their governments are doing. So access to information is very important. From our side, The World Bank has been working on this issue for a long time, and remains a critical part of what we do. We have done over the last five years, $23 billion in 119 projects that have a component on transparency or accountability or good governance. This remains at the core of what we do, and we do it through our different operations, we do it through our policy dialogue with the authorities, and we do it throughout all our internal policies on how we do procurement and fiduciary. In Brazil for example, we work with the government and supported an artificial intelligence system that actually can link different databases that are public and some others that are not public, and through that system identify potential fraud in tax administration. That same type of approach to technology can help on procurement, can help on many audit aspects of a country, and again, can bring some light from the supply side on what's happening. In Bangladesh, we're working with authorities to publish all procurement data online, all purchase of goods and services. Again, bringing light to that aspect. In Ukraine, in partnership with a number of players and other partners, we support the establishment of a high anti-corruption court. In Mauritania, we helped to set up the Financial Intelligence Unit to fight money laundering. Here, it is another aspect, another side of the coin on corruption. Anti-money laundering, our own initiative here at The Bank on Stolen Assets Recovery Initiative, and overall the agenda that we have on illicit flow of funds. This is the other side of the coin. There's rent seeking on one side that takes money out of activities, and then you have to follow the money, where it goes outside the country. We are trying to tackle that from all aspects. And of course, The Bank has continued doing an analytical work on this and also like this event, gathering players and partners that are interested in this agenda. We have done that through the Anti-Corruption for Development Global Partnership, that today has more than 50 partners that have joined. This agenda is definitely not easy. You know better than anyone else that have been engaged on this. Opportunities for corruption are everywhere, and our approach is to tackle those aspects, first from the supply side on every aspect that generates an opportunity through our operations, through our policy, through our analytical work. But also, we need to focus on aspects that foster the demand side of it, as I mentioned earlier, so the citizens get engaged on this agenda. That's the only way to build trust on both sides. With that, I know that you will have two very interesting days and we'll discuss many of these topics and many more topics in a lot of detail, so I wish you very productive discussions. Thank you.

[audience applauds]

[Simon Fowler]

Thank you very much Pablo. So just to get you into the mood, if you're not already in the mood, we could to just run a little audience poll just to find out what you think about this topic, and make sure you are in the right room. Please take out your phones and scan this image you see. I will move out of the way. We have a couple of questions, and I'm assisted by Mark over here, he's our tech wizard and we're going to ask a couple of questions. The first one here is a little bit sort of frivolous. I want to understand whether you can get into the software, first of all. Since we're talking about anti-corruption, nobody can see your answers except us up here. So this is completely anonymous, I promise. Are you excited to be here? Are you cool as a cucumber? Are you hopeful about the outcomes? Some of you had just had coffee. Could you please give me a second, because I'm not ready, and are you worried about the state of this topic? We have a clear winner, "Excited to be here." That's good. You are all in the right place, right? Good, excellent. 10 of you are cool as cucumber. Excellent, that's very good, because it's summertime, we like cucumbers. Let's move on to a more serious question. "Which segment of the anti-corruption community do you represent? Development partners, local or central government, CSOs, academia, private sector or other." Perhaps you are not even listed there. We have a large other category. So who are you, the others? Anybody want to shout out quickly? Don't be shy. Press, maybe. For those of you watching in World Bank Live, you can join us with this too of course. Let's move on to the next question. "Where do you work in anti-corruption?" Here you've got three choices, actually four. Are you in all of the above? And we are going to do a number of polls throughout the next… and I'm not going to say two years this time, because we're only here for two days, I do promise that, because some of you got tickets to leave and go home again, right? We are here for two days, but during these two days, we'll be doing a few polls just to keep your energy and your attention, and just to find out what you think about different topics. All of the above is winning here. Excellent, good. A lot of different technical views here. The last question, please. This is what we call a word wall. You can write a short answer here. Is there one more question? "What outcomes do you wish to achieve by attending this forum?" And this is very interesting I think for our speakers, especially for our first keynote speaker and for our moderator who I'll introduce you in a second. What do you hope to achieve by attending this? We want to network. "We want to learn from each other. Collaboration is key. We want to have new ideas to implement in my own country. Develop some urgency. New insights. Collective action." I believe that's exactly why we are here. This is about collective action, learning from each other. Assuming that we don't know all the answers yet, together we can form partnerships to try to solve some of these questions. Anything else? It seems to have stopped there. Is that that good enough? All right, thank you very much for playing along. With that, I would like to introduce our keynote speaker. Let's go back to our slides, please. Keynote speaker is Francis Fukuyama. Mr. Fukuyama, please join me on stage. It's really nice up here.

[audience applauds]

[Simon Fowler]

Pleasure meeting you. Please make yourself comfortable. You have a choice of two. Then as our moderator today for the next 55 minutes, would you please welcome Martin Raiser, who is the Regional Vice President for South Asia at The World Bank.

[audience applauds]

[Martin Raiser]

Nice to meet you, sir.

[Simon Fowler]

Good morning, nice to meet you. Both microphones are ready and I'll leave everything in your capable hands. I'm here if you need me.

[Martin Raiser]

Do you just want to start this? I think we will hear first from Professor Fukuyama, and then I think my role is to ask the questions you don't dare to ask, or maybe at least to ask some questions, and I look forward to the discussion. Thank you.

[Francis Fukuyama]

Thank you very much, Martin. I want to thank the Governance Practice for inviting me. This is a really important topic. I've seen already quite a few old friends and I would say, everybody in this room is doing God's work. It's important that we do this collectively and do share knowledge. Let me just say a few introductory things about corruption, and put it in a little bit of a historical and cross-national perspective. What is corruption? The standard definition, it's the diversion of public resources for private gain. But under that broad heading, there's actually several different phenomena that have very different approaches that are necessary. The most obvious is just pure theft of state resources. This can go all the way from petty corruption in a customs agency all the way up to what's called state capture, in which the major institutions of the state are actually controlled by people who don't have any interest in public benefit but want to use it for completely private purposes. This was supposedly a characteristic of the previous president in South Africa, and it continues up to the present day. There's another form of corruption that is more related to politics. There was a book called Violence and Social Orders by Doug North, Barry Weingast and John Wallis, that talked about the role of rent seeking coalitions in stabilizing conflicts. Basically, you can either fight over resources or you can agree to share them. But in the process of sharing, you essentially get to exploit those resources for your own gain. If it's a question of whether it's better to be in a civil war like the one that was in Bosnia or a peaceful situation like the one that appeared after the Dayton Accords, you're probably better off being peaceful, but it means that you've in a way fed a lot of rent seeking because that's the basis of the peace. There is another form of corruption that acts as a kind of lubricant for dysfunctional states, where the state procedures are so cumbersome that paying a bribe will get you the license or procure an outcome that you want more easily. If you're in an emergency crisis, you oftentimes want to disperse funds quickly. If you have to fill out all the paperwork and do the due diligence, you're not going to get effects. That's a potentially good solution, but it's covering over a very dysfunctional state. Then there's a final form that I think is extremely common. It's a form of democratic politics, called clientelism, in which a politician trades individualized benefits in return for political support. Now, there's a view, especially in developed countries, that corruption is something unusual that happens in certain countries that are highly dysfunctional, and the normal state of the world is clean government. This is just completely ahistorical. I would say that most governments through most of human history have actually been in the business of holding power in order to extract rents. It's actually a kind of modern phenomenon that you get governments that actually think that they're operating in public interest. This was true in the United States. Beginning, especially in the 1820s, virtually every official appointed to a federal agency in the United States was there as a payoff from a politician. This is a problem that lasted in the United States for nearly 100 years. I'm going to come back to this because the way that the US dealt with this problem may be a model for other developing countries today. But if you're suffering from this kind of rent seeking coalition or this kind of clientelism, you have to recognize that this in a way is a normal way of doing business and you have to take special efforts to combat it. I had a little section on the bad economic effects of corruption, but that's been dealt with already in the introduction. I would just say that in addition to the regressive tax that corruption constitutes, taking money from the poor and giving to the rich, it also has very deleterious political effects. It fuels a layer of elite oligarchs, it affects the outcomes of elections. Corruption often spreads from stealing state resources to other forms of criminality. Finally, in line with the overall theme of this workshop, it breeds a generalized distrust, a feeling that all politicians are in it for themselves, and that there's really no trustworthy institution to which they can return. That in turn is a breeding ground for populism and for various other forms of very counterproductive politics. In terms of dealing with corruption, I think the solutions depend very much on what type of corruption you're dealing with, and there are different fixes. If you look at petty corruption up through procurement, some of the kinds of issues that have already been mentioned, I think that there are effective solutions. The one that has been the most prevalent, I think, over the last let's say 15 years, is some form of transparency plus accountability. This can be based on technology. In Ukraine for example, they had this very successful procurement platform called ProZorro that helped in exposing a lot of corruption there. I think that one of the lessons if you look at the overall literature on the impact of transparency is that, by itself, it's not sufficient to actually beat back corruption if it is not tied to concrete accountability mechanisms. People can find out about corruption, but if they don't actually have a political means of holding the officials that are corrupt accountable, that information isn't going to do any good, and therefore, you need to think about the politics of accountability as well. If the corruption is a result of a power-sharing deal that has settled a conflict, that in a way is much harder to deal with, because if you undo the political settlement and the rent seeking coalition, you're threatening to go back into the same conflict that got you into that situation in the first place. One of the dangers of that kind of situation is that it's not transitory. It hardens into a kind of permanent power-sharing. I think that Lebanon is the classic example of this, where in order to solve the sectarian divisions in that country, there's a consociational division of power that nobody can do anything about at the present. You can have corruption countered by modernization, because as a society modernizes, you get civil society groups, you get a business sector, you get different actors in the society that actually want effective government. They don't want to have to pay bribes. That was very critical in the American story beginning in the 1880s, when you had a big civil society movement arise led by the business community that actually wanted to have clean government. That was the basis of the progressive era coalition that did things like pass the Pendleton Act that put the American Civil Service on a merit basis rather than a patronage basis. The final point I'd like to make is one I've been thinking a lot about, which is that ultimately, I think the solution to corruption is state building. That is the creation of a modern impersonal, high-capacity state. Now, state capacity and anti-corruption are related, but they are not the same thing. Obviously, if you have a highly corrupt state, it's not going to effectively deliver services to the population, but it's possible to have, for example, a relatively strong state that has a high degree of corruption. That was China, particularly before Xi Jinping's anti-corruption drive where the state was actually producing good outcomes, but there was a lot of corruption. You can also have an uncorrupt state, in which the state is kind of feckless and weak. I would say that Moldova under Maia Sandu right now has got a very good, uncorrupt top leadership, but it's an extremely weak state that has a lot of trouble dealing with the kinds of challenges that it's faced. I think if you look at the history of modern states that have managed to grapple with the issue of corruption, a lot of it really has depended on state building. Where did the incentives for state building occur? I think that a lot of it actually has to do with things like military competition. This was true in ancient China. It was true in early modern Europe. It's true in Ukraine today. If you think about what's going on in Ukraine, given that they're in an existential fight for their lives, if you steal resources at a moment when you and your family could get killed as a result, you're going to turn to public interest rather than to private gain. I think that one of the other alternatives is the one that I just mentioned, which is as a result of effective leadership of a civil society political coalition, you can push for reform of your political institutions. But the state capacity is still really important because people care about outcomes. They don't simply care about procedures. If the state actually delivers outcomes, then it's going to have more trust and it's going to be seen as more legitimate by citizens. I guess the final point I'll end with is the question of political power. That explains in many respects why a lot of efforts by development institutions have had rather disappointing results over the past, let's say 20 years. Corruption exists because it is in the benefit of very powerful political actors to be corrupt. If you don't dislodge those political actors, you're not going to really deal with the problem. Generally speaking, the outsiders don't have enough leverage just on their own, let's say through loan conditionality, to really push these people out. All you do is push corruption into a different part of the government, but it really stays the same. That means that the fundamental political power that will actually defeat corruption has to be generated internally. It has to come about through a coalition of internal actors that really want an uncorrupt political system, and that requires leadership, organization. The outsiders can help, they can provide technology, they can provide advice, but fundamentally that political coalition has to be driven internally. Therefore, I think the development institutions have to look for opportunities that are being generated by the domestic politics in all of these different countries. If you don't solve the problem of corruption, I think you've got a really big problem. We've seen this general erosion of trust. There are many polls and indicators that have shown that across the world, trust in governments has been falling very dramatically over the last 40, 50 years. That includes rich countries. It includes the United States, where social trust and certainly trust in government is at historic lows. This is really what breeds populism, because what populists say is that there is an elite conspiracy that doesn't take the interest of ordinary citizens into account, and we are being manipulated. Indeed, if there's a high level of corruption, they are being manipulated. Therefore, I think that for a healthy democratic politics, if you don't solve and address both of the issues of corruption and of building state capacity, you're going to end up in a very dysfunctional form of politics. With that, I look forward to our conversation.

[audience applauds]

[Martin Raiser]

Thank you very much, Frank, for these opening remarks, which set the scene, I think very well. I should have corrected myself. The questions that you don't dare to ask, you should dare to ask because I will only ask a few and then I'll open up to Q&A. I feel a little intimidated, frankly, sitting on stage next to you because I'm a great admirer of your work, particularly the long historical analysis of how effective states were built in the west. Applying that knowledge to development and trying to think about how can effective states be built, but also trying to reflect on why in the west we're starting to see an erosion of effective state institutions, I think is a really fascinating topic. I'd like to perhaps ask you three broad questions before we open it up to the audience. The first question relates to this idea of corruption as part of a political settlement, and the question of how do you envisage positive transitions out of such a settlement and what can be done about it? I think I know more examples of negative transitions. I'm thinking in my region in Afghanistan, clearly the transition was in the wrong direction. All attempts to build an effective state failed, and one could argue were ultimately undermined by the inability to build a political settlement that was not reliant on corruption. But I'm curious, do you know from your experience a good example of a political settlement that developed in a positive direction?

[Francis Fukuyama]

Well, in a certain sense, all modern governments came out of political settlements. Like I said, rent seeking coalitions are not something new that just happens in a few selected developing countries. This was really the situation of most politics in most European countries at an earlier stage in their history. I think that what tends to happen is that the society is put under stress, and the kind of rent seeking coalition that produced stability in an earlier period is no longer adequate. Just to give you current example, again, I don't want to constantly refer to Ukraine, but Ukraine's big problem before the war started last year was that its economy was controlled by a group of about six or seven oligarchs, who had made their money as a result of the dysfunctional privatizations that occurred at the time of the collapse of the former Soviet Union. And really, that was the driving source of corruption in that society. Today, those oligarchs are really on thin ice in many respects, because if they continue that kind of activity... Rinat Akhmetov has actually seen his net worth fall by three quarters because his steel plant in Mariupol was bombed by the Russians. It provides this big opportunity actually for a shift out of that rent seeking coalition into something better. If the Ukrainians are smart, they will take advantage of it. Now in other places, you can't wait for a war and the physical destruction of assets for this to happen. That's I think where the kind of modernization coalition comes in, but I'm having a little bit of trouble thinking about a recent example where that has happened, because as I was saying, the problem is that once you create that kind of coalition, it tends to harden over time. As the society develops, it becomes more and more dysfunctional and it actually creates its own dysfunctions that could then lead to a further relapse.

[Martin Raiser]

I guess one tentative conclusion in the search of still positive transition examples is that one ought to be very careful in negotiating political settlements to make settlements that are built around corruption. Would you say that we should not accept it? Because we are constantly in fragile and conflict states facing the need for us to decide, is this acceptable enough? Or does it create the risk of creating these negative transition parts further on?

[Francis Fukuyama]

Well, look, as I said, a lot of times the reason that you develop these settlements is because the alternative is violence. You want to stop the violence, and that's an urgent priority and the rent seeking coalition is an alternative to war, but it takes a long time really for that then to evolve into something like a more public facing state. I think that people's expectations for how rapidly that transition can happen are sometimes a little bit elevated.

[Martin Raiser]

I want to turn to another point that comes out of your work, particularly the historical work, which is the question of sequencing. I think you say in one of your contributions or perhaps in several, that there is a risk of prematurely opening the franchise before an effective state has been built. That that can be a source of clientelism. So effectively, the push for stronger democratization, for electoral processes in countries with weak states may lead to political strategies for winning votes that are based around the distribution of rents and favors. Could you elaborate on this? Do we need to put democracy on the back burner until effective states have been built if we want to avoid that risk?

[Francis Fukuyama]

Well, the short answer is no, but it's important to keep in mind the history of this. Many modern effective states have been built by authoritarian regimes. China is a clear present-day example, but you look at the current German bureaucracy. Where did that come from? It was inherited from the Prussians, who established a modern bureaucracy a couple of centuries ago. And then they give it as a gift to the Democratic Germany that appears in 1949, and the traditions of that professional bureaucracy remain in the Democratic period. Now, I don't want to cast aspersions on any particular countries, but if you look around Europe, both Greece and Italy actually democratized before they had an opportunity to consolidate a modern bureaucracy. This is an argument that the political scientist Martin Shefter made many years ago. Under those circumstances, there's a huge amount of pressure to basically use clientelism as a way of gaining votes. This is exactly what happened in the United States. America has never had a Prussian style modern professional bureaucracy. It still doesn't in many ways, but certainly it didn't have that in the 1820s when the franchise was open to all white males without property qualifications. You had millions of new voters coming in, and what did Andrew Jackson and his successors figure out? The easiest way to get people to vote for them was to bribe them, give them a bottle of bourbon or a Christmas turkey or job in the post office. This was the practice in American government for much of the succeeding 100 years. I think that you see a lot of those problems occurring in Southern Europe again because both Greece and Italy opened up the franchise before they had really consolidated this kind of modern professional bureaucracy. That doesn't mean you can't get there. The United States got there and actually, both Italy and Greece have made certain strides in that direction, but it is a problem. Now, the reason I say it's completely irrelevant to the present is that there's nobody in the world who's in a position to say, "Oh, okay. We're going to delay democracy for 20, 30 years. We're going to build a powerful modern bureaucracy and then we're going to open up the franchise." It's ridiculous. Nobody can do that. Nobody's in a position to, because the expectations of people are for democratic participation and their right in demanding that. Therefore, sequencing whatever its role may have been historically it is not relevant to our current practice and we have to try to do everything simultaneously.

[Martin Raiser]

Sounds like a challenge. Maybe the third question that I would ask you is picking up a debate that I think amongst development economists has been quite prominent recently, which is this question of effective leadership show. Stefan Dercon, for example, has argued that development only happens when the ruling elites want to develop, when they have a vision of development. But others have argued that waiting for that effective leadership may be a bit of a fool's errand. I mean, you may not always have in your country's elites with the necessary power and the necessary coherence and a development vision. In the absence of that, can coalitions for development be built? Could we think of islands of excellence from which better practices spread, and that can generate a shift in expectations that a deed a better way of governing is possible? What is your sense of that? Because if the first one for us in the development community is often difficult to control, the second one, we may have some agency over. Can you give us some hope?

[Francis Fukuyama]

Sure. Well look, the question of leadership and that underlying capacity and grassroots support are completely interactive. Oftentimes, if a leader sees that anti-corruption is actually the root to power, that may actually make the leader forthcoming with an agenda that will actually be positive for the society as a whole. But I do think the leadership is ultimately necessary, because it's not just kind of citizens deciding to participate in an election or something. If you really don't have an organized coalition, you're not going to really going to generate sufficient political power to overcome all of the entrenched actors that are keeping the society corrupt. That usually requires really three things. It requires leadership at the top to organize the coalition, it requires grassroots support from the bottom, and it requires an idea. It requires a concrete vision of what an uncorrupt high-capacity government looks like. If you don't have the three of those interacting, I think it doesn't mean that you shouldn't build the grassroots support, it doesn't mean that you shouldn't push the models that you want, but it may not come together at any given moment, but at some point, it will. That's why you need to work in all of those areas.

[Martin Raiser]

Great, thank you so much, Frank, for these elaborations. Let's open it up. I can see hands up, so I'm going to go first to the gentleman over there with the blue shirt and the glasses. Yes, it's you. You're looking around, it's you.

[Simon Fowler]

Please use the microphones on the tables. Thank you.

[Peter Evans]

Sorry, I was looking for a showbiz mic, but my name's Peter Evans. I'm the director of the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Center. Firstly to say, a great session and it's brilliant for us political economy animals that the politics is here in the first session. I guess for those of us who largely work on corruption issues in other people's countries, could we all be a bit more overtly political when talking about corruption challenges and what to do about it? Because I was kind of expecting the politics to come up in day two, in terms of talking about the political economy reality. It's great that we're front and center in the first session, but is there behavior that we could do differently? Are there other things that we could do differently, to make sure we don't lose this focus on politics? Thank you.

[Martin Raiser]

I don't know if you want to answer?

[Francis Fukuyama]

Well, okay, let me just respond to that. Another phenomenon that I haven't talked about is something that I labeled with a very long word in my Political Order books, which is re-patrimonialization. That is to say, because rewarding friends and family is a natural form of human sociability, even if you get to a modern state that has a professional bureaucracy and is supposedly operating in public interest, that doesn't mean that you can't go backwards and that there won't be powerful incentives for players to re-patrimonialize the state and re-corrupt it. I think that we're seeing examples of that in the United States. If you look at some of the things our past president was doing, it was basically clientelism. You only do emergency disaster relief for states that voted for you, this sort of thing. I think that first of all, it should make people that live in developed countries a little bit less arrogant about their own systems, and recognize that they are also subject to backsliding and dysfunctional government. But it means that can't ever relax, because the moment that you think you've defeated corrupt forces in one sector, they're going to reappear because I do think that there's a sort of natural tendency. In a way, a modern state is a little bit unnatural, the idea that you should hire somebody on the basis of their qualifications rather than hiring your cousin or your son-in-law. That is something that we see all around us today.

[Martin Raiser]

Yes, please.

[Mark Robinson]

Thank you very much. Mark Robinson, Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. This is a question for Martin and Frank. Over 25 years ago, the late president of The World Bank, Jim Wolfensohn, gave a landmark speech, The Cancer of Corruption. 1997, I think it was. In the quarter-century that's passed since, the question on my mind and I'm sure others in the room is, what has been learned since within The Bank? What has worked and what has not worked and what lessons do we take away from that to inform our conversations today and tomorrow? Thank you

[Francis Fukuyama]

One up.

[Martin Raiser]

It's a good one. I can only really speak with confidence on countries that I know. I worked in Uzbekistan, Ukraine, Turkey, Brazil and China, and now I work on South Asia, but it's a region I don't know very well. I do think we have a lot of positive examples in the areas that Pablo mentioned in his introduction. I think we've gotten much better at using technologies. We've gotten much better at tracing the money. We can analyze value chains of public procurement and we can look at the weak links. I think we have less positive experiences, but some in building up bottom-up accountability. The citizen engagement plays a much stronger role in a lot of our operations, and in many cases, in a very positive way. I don't think we have fundamentally learned how to build effective leadership or how to build coalitions for change. I think Peter Evans asked us to be more overtly political. It's very hard for The Bank to become an explicit political actor, and so that makes it difficult for us. Very often, I think we should be honest that we don't fully understand the local politics sufficiently, to be able to even be an actor if we wanted. My own experience in the five countries that I mentioned is, I felt much more confident about reading the local politics in the countries where I spoke the language. In Ukraine, I was able to move around the local language. The same in Brazil. I was not able to do this in Turkey and China. You can argue that Turkey and China are much more complicated places, but as Debbie will confirm, even Brazil is not for amateurs. I do think that local knowledge makes a big difference for our understanding of the local politics and our ability to navigate within them, perhaps to use them for our advantage to build coalitions in support of reform. There's a very interesting book on procurement reform in the Philippines by someone called Edgardo Campos, that describes in some detail how The World Bank together with USAID built a coalition for a very controversial reform. I think it would be great to have more such examples. They do exist, but they're rarer than I would like.

[Francis Fukuyama]

Yeah, if I could say, so one of the organizers of this conference, Francesca Recanatini and I wrote an article together 20 years after the Cancer of Corruption Speech, what was the impact? We noted that it was disappointing in many respects. And again, the reason it had to do with what I just mentioned, which is that there was insufficient political power to really overcome deeply entrenched corrupt actors in many parts of the world. However, I would say that there are areas where things have gotten a lot better. I mean just in terms of state capacity, central banks and finance ministries are simply miles ahead of where they were 30, 40 years ago. The time of the debt crisis in the 1980s, you had a bunch of incompetent central fiscal institutions and that tends to be much less the case. Procurement is another area, where there are certain technical fixes that can be very useful. The other really important area I think is in tracing illicit money, because the focus on money laundering and the complicity of western financial institutions in helping to launder corrupt money was scandalous in the first place. But that's actually an area where western countries, if they really politically want to do this, can make some contributions. I think you've seen some gains in that area.

[Martin Raiser]

Let me just see a show of hands, maybe we accumulate three... Oh my goodness. We have five minutes and six questions. I think I may have to choose. So you're first, then we're going to go to you. I'm sorry?

[Simon Fowler]

Choose some ladies.

[Martin Raiser]

Yes, we go to you first and then to the lady with the glasses, and then we go to Debbie and we finish with you over there at the back. I'm sorry that the rest will have to wait. Please.

[Haykuhi Harutyunyan]

Thank you so much. Haykuhi Harutyunyan, Armenia Corruption Prevention Commission, institution newly established after 2018 change in the government. My question is for Professor Fukuyama, because he knows how I was inspired being at the Stanford University, and actually that was a driver. I took position at a public institution and I applied all the knowledge. Now I'm hearing kind of new things for myself, like countering corruption through state building. But I want really to ask to elaborate more on that, what actually it means in practice when your country where you, exactly as you mentioned, have a strong leadership but weak institution, you have a fragile environment and ongoing war. Where should we start with building the state? Thank you.

[Martin Raiser]

Are you happy taking three?

[Francis Fukuyama]

We should collect [inaudible].

[Martin Raiser]

Yes, let's take three. We have actually until a quarter past, so I think I can take all of you if the questions are short. So we go to the lady with the glasses over there.

[Alina]

Yes. Hello. My question really is about this change of environment, because we are discussing like we are still in this big corruption against development paradigm, which we were part of it for the past 30 years. But the world has been changing radically in the last year. So now, we have corruption declared by the Biden administration as an instrument of foreign policy of hostile powers like China and Russia. In response, we are going to weaponize anti-corruption, in order to defend the world. But I mean, do you think that this salience these days of anti-corruption as an international policy tool where the number of sanctions is higher than it's ever been and all these new tools coming in, are actually helping solving our old problem of corruption as an obstacle to development? Or in fact, as I thought you alluded earlier, it's actually risks increasing instability. Thank you.

[Martin Raiser]

Can we take one third one, Debbie?

[Debbie Wetzel]

Thank you. I'm Debbie Wetzel, Former Senior Director of Governance here at The Bank, and now an independent consultant. Frank, you talked a lot about the importance of high state capacity. But this term, state capacity, it would be useful if you could unpack that a little bit for us. Thanks so much. What does it mean?

[Francis Fukuyama]

Right, sure. To Haykuhi's question, unfortunately Armenia is in a really tough situation. I think that the most important obstacle to really making institutional progress is really geopolitical. The fact that Armenia has been dependent on Russia for its security, but it's not a very good patron and certainly is not one that's going to encourage institutional reform, makes things very, very hard. I would say that what you've got to do is just keep working to build that domestic capacity. Not only in your own anti-corruption organization, but in terms of that basic state capacity, to deliver services and over time, train enough people. That gets to the question of what is state capacity? State capacity is just people. It's really just people. It's having people with the right education and skills to actually run the government effectively. If you look at the major instances of state building, I covered a lot of this in the second volume of my book in Britain, in Prussia, in France, in the United States, all of the big state building initiatives were connected to a reform of higher educational institutions. In Prussia, for example, the Humboldt reforms and education were critical to their state modernization. The reform of Oxford and Cambridge in the middle of the 19th century was important in feeding the British Trevelyan Northcote. The French created these ENA and a whole series of major educational institutions. That's one of the things that I've actually wondered about The Bank's education policy, because for understandable reasons, they have focused on basic K-12 education. But actually, if you look at a lot of these development success stories, it came about as a result of actually developing an elite that could actually run the government effectively. Now, to Alina's question about sanctions, well, there's sanctions and there's sanctions. Some sanctions have actually been pretty effective. I think against South Africa, against Libya, they both worked, but the overuse of sanctions, I think in the long run is going to lead to diminishing returns, and particularly when they're used to deal with an issue like corruption, because it's so central to the well-being of a lot of the local political actors, individually important. It's not something that is necessarily going to be terribly effective. Then there are all sorts of knock-on effects of the overuse of sanctions, what it does to the dollar and what it does to the legitimacy of the United States and other developed country actors that try to employ it.

[Martin Raiser]

Great. Let's go for another round. Are you still interested, gentleman over there? Yes. Yes, you. Yeah, the one waving at me. Yes, absolutely.

[Dr. Ahmad Anwar]

[Speaking in foreign language]. Good morning. [Speaking in foreign language]

[Martin Raiser]

If you're going to speak in Arabic, I think Mr. Fukuyama and I will perhaps need translation [inaudible] those people. Are we able to do translation?

[Simon Fowler]

We are not, no.

[Martin Raiser]

Okay, so I'm sorry sir, but maybe one of your colleagues, you could explain your question to one of your colleagues who can say it in English and translate it back to you. In the meantime, let's go to you, sir.

[Dr. Ahmad Anwar]

[Speaking in foreign language]. Good morning for all.

[Martin Raiser]

Okay. Good.

[Dr. Ahmad Anwar]

[Speaking in foreign language].

[Simon Fowler]

We won't be able to ...

[Dr. Ahmad Anwar]

Yeah.

[Simon Fowler]

We have translation [inaudible]. We can translate.

[Translator]

Dr. Ahmad from Kurdistan region of Iraq.

[Martin Raiser]

Perfect.

[Translator]

Commission of Integrity.

[Dr. Ahmad Anwar]

[Speaking in foreign language]

[Translator]

I want to just ask a question.

[Dr. Ahmad Anwar]

[Speaking in foreign language]

[Translator]

The problem of corruption is actually something important here in our region.

[Dr. Ahmad Anwar]

[Speaking in foreign language]

[Translator]

The problem is the governor actually looks like he suppose everybody and the citizen is included to him.

[Dr. Ahmad Anwar]

[Speaking in foreign language]

[Translator]

And corruption crimes is actually considered as the desire for collecting money in illegal way.

[Dr. Ahmad Anwar]

[Speaking in foreign language]

[Translator]

And our path in that concern is considered so long, in order to rebuild the state and the law.

[Dr. Ahmad Anwar]

[Speaking in foreign language].

[Translator]

And I think that even in the developed countries, the sovereignty of law is also a matter that is taken into consideration.

[Dr. Ahmad Anwar]

[Speaking in foreign language].

[Translator]

The question here is, how can in our developing countries, can we rebuild and find a radical solution for that problem to rebuild our state and fight corruption and end these crimes of corruption?

[Dr. Ahmad Anwar]

Thank you.

[Translator]

Thank you.

[Martin Raiser]

Thank you very much. Let's go to here and then I can take I think two more. We'll go here and over there and now, and then we close. Please, go ahead.

[Ravi Prasad]

Thank you. I'm Ravi Prasad From Transparency International. I have a question for Professor Fukuyama. You mentioned about a coalition between civil society and leaders that can be effective in countering corruption. Unfortunately, in our movement, which is spread around the world, what we see is the civic space is shrinking. Anti-corruption activists are constantly under attack. In terms of leaders, we see every election in this world is contested on the plan of anti-corruption. The moment they come to power, it's forgotten. Any solutions, sir?

[Irene Charalambides]

Thank you. Well, I heard you talking before about…

[Martin Raiser]

Introduce yourself briefly, if you…

[Irene Charalambides]

Yeah, sorry. My name is Irene Charalambides. I'm Vice President of Organization for Security and Safety in Europe. You talked a lot about fighting corruption, but what about political will? Can you really fight corruption when there is absolute non-political will, and there is a huge gap between policies and implementation? And what do you do when the institutions are undermined because there are people there appointed by one man, a president of a republic? And then instead of serving the people, they are trying to serve the person who appointed them. Especially in small countries, when it comes to media who are quite responsible for checking on government policies, then the media, it's easy to be controlled by governments. We are going round and round in circles, and we cannot do good practices. We cannot implement good practices because of the political will not being existent. Thank you.

[Martin Raiser]

You want to take these three.

[Francis Fukuyama]

Okay, yeah.

Martin Raiser:

And then take one final.

[Francis Fukuyama]

Okay. The gentleman from Kurdistan, there's no generic answer to your question that will apply to Kurdistan and other countries, because your situation in Kurdistan is very context specific. I've been there a couple of times. I know something about the internal dynamics of the two big political parties, and that creates a problem for building a kind of centralized state institution. Maybe we could talk about this individually, but it's not something that I can... I'm not sure I can give very useful advice. The question about the shrinking space for civil society, so my activities over the past two decades have actually focused less on economic development and more on democracy promotion and human rights promotion. I was a board member of the National Endowment for Democracy for 18 years. I'm now on the board of Freedom House, and there's been a declining democratic space for 17 years in a row since about 2008, which is documented in Freedom House's Freedom In The World Reports annually. Yes, we need to push back, not just on the issue of corruption, we need to talk about human rights and human freedoms in general. How do you do that? It's very complex. Part of it is geopolitical, because you've got these two big actors, authoritarian great powers that are pushing an anti-democratic agenda. You've got a lot of ambitious actors in individual countries that want to use corruption as a tool for themselves. And you've got this weakness, I think, in a lot of developed countries. So the United States, because of its internal political problems, has not been the kind of model that it would've been 20 years ago for other countries. I think a lot of people outside the United States say, "Well, maybe you Americans should go solve your own problems before you lecture us about democracy." So there's many different elements to this about how you push back, but I agree with you that the struggle against corruption is one important part of a broader set of issues. Now, on the question of political will, I don't like the term political will because it kind of makes it seem like it's an individual issue for some leader to get up and just say, "Okay, I'm going to do the right thing today because I've had a good breakfast and I feel really strong." Political will is about coalitions. It is about building an alliance of actors that want the same objective that you do. If you have a small country with a president that doesn't want to do things and that office is very powerful, it's going to be really hard to do that. I don't have a particular suggestion for that, but generically, this is why we actually need to start a discussion at the World Bank on corruption, talking about the political economy of corruption, because if you don't deal with the politics in the first instance, you're never going to make any headway in this. What you need to do is think about where do I get allies? How do I mobilize civil society, citizens, other people? Where do we find the leadership? What organizational form, what kind of external support can we get? That's what constitutes political will, and that I think really needs to be the focus of all of the actors that really want to deal with corruption.

[Martin Raiser]

Great. I think we have time for one final really quick question. I'm going to go to the front table there. Sorry for the others, apologies.

[Arkan]

Yes, it's working. Thank you for the opportunity. My name is Arkan. I'm representing the United Nations Development Program, UNDP. My main area of work is in the Middle East and North Africa, so I'm responsible for the anti-corruption programs there. Of course, there are standards, evolving standards on anti-corruption, good practices, lessons learned, but as you rightly said, supporting anti-corruption is highly dependent on also understanding the context. In highly complex and highly volatile situations, what role can really international organizations or organizations that are by nature risk averse, short-term projectized and mainly concerned about delivering grants, loans and smaller type of more concrete development assistance? What role can they really play in actually tackling this problem, that by nature requires some risk taking, some longer-term vision, and also the ability to think in terms of trade-offs between delivering and actually supporting reform? And then putting that in the context of the return of geopolitics, which has been raised beyond sanctions. Also, do you see now this kind of polarization, more opportunities for expanding the anti-corruption global movement, or actually risks that it can be shrinking because of this kind of polarization in terms of geopolitics? Thank you.

[Francis Fukuyama]

Well, as you yourself noted, there's no generic answer to your question about what development organizations can do. It really depends on the country. I would simply note that you shouldn't look back at the past 20, 30 years as a failure because as I said, there are specific areas in which help from The World Bank, from UNDP, from other organizations actually did succeed in building state capacity. As I said, central banks, finance ministries, they're very technocratic agencies, but a lot of work has been done there and there are other areas where that can happen. I think that what's important to recognize is, as I was saying, the fundamental driver of improved institutional performance has got to come from within the country. The external partners have to really see themselves as partners to work with those domestic actors, because they're really the ones that are going to both not only address the problem, but they're the ones that can actually define the problem best. That's where the fundamental action, I think, is going to have to come from.

[Martin Raiser]

Thank you very much, Professor Fukuyama. I think this was a discussion that probably could continue, as the hands of participants that wanted to ask questions and didn't get a chance suggests. But I take away a strong plea from you for us to take politics seriously. That's something that I very much agree with. We have to move beyond the fiduciary, beyond the PFM, beyond the technical assistance to engage in the politics of state building and development, if we're going to overcome the problem of corruption. Many issues we didn't touch upon, such as the reason for the deterioration of trust in western societies, even those where corruption ostensibly is still quite low. It's not, in my view, just directly correlated, but we'll leave that discussion for another day. Thank you for giving me the chance to moderate. It was a real pleasure to have you here, Professor Fukuyama, and to all of you, a nice forum. Thank you.

[audience applauds]

![[Backup] WBLive_landscape_All-colors - 1](https://s7d1.scene7.com/is/image/wbcollab/trending-World-Bank-Live-landscape?qlt=75&resMode=sharp2)