Teach Children in a Language They Use and Understand

Read the transcript

- 00:05 [Femi Oke]: Hello everybody. My name is Femi Oke.

- 00:08 I am going to be your moderator for the next 90 minutes. Children. when they're taught at school

- 00:14 in the language that they speak at home, do better in their school studies. It's just the fact.

- 00:21 I have been a journalist for many, many, many years, decades in fact. And about 13 years ago, I

- 00:27 was reporting and living in South Africa and a new keyboard had been designed and the keyboard was

- 00:33 not a keyboard full of English characters. It had the characters of the languages that the children

- 00:39 were speaking at home. Instantly, homework got better. It came in on time. The students study

- 00:46 better because they could type in characters that they understood in a language that matched

- 00:50 the languages they spoke at home. So the reason we're all here is because as the World Bank has

- 00:56 put out its first policy proposal for language that is important, that children speak at home.

- 01:08 [Femi Oke]: So we are going to be talking about that.

- 01:11 And in this conversation we will have, are bank officials, academics,

- 01:17 we have ministers and we will also have you, you see that little chat box there, your comments,

- 01:23 your questions, you can put them in the chat box. We have a World Bank team who will be looking at

- 01:28 those comments, questions, answering them, and also bringing those conversations, your

- 01:33 comments. I will bring them into the conversation here because we are a multi-lingual conversation.

- 01:39 We will have interpretation in French, Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic, and also

- 01:46 in English. So now that we're all set and we're ready to go. Welcome everybody to Loud and Clear,

- 01:54 teach children in a language they use and understand.

- 01:58 [Female voice]:

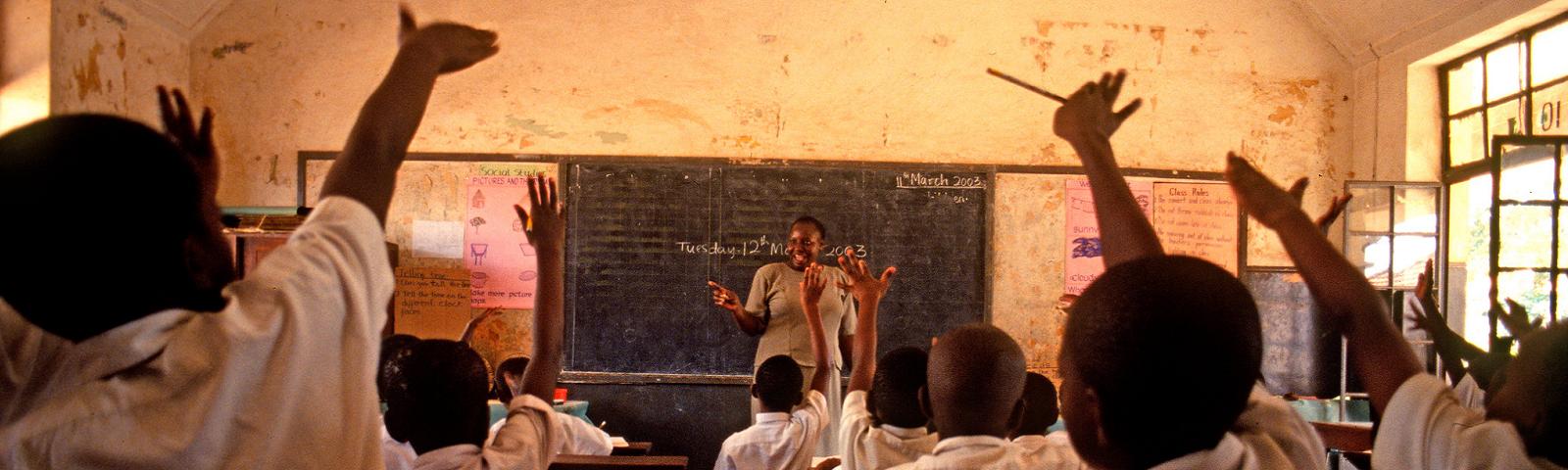

- 02:02 Think back to your school days, you may remember your classroom supplies mates, a favorite teacher,

- 02:10 even a principal. The teacher would explain the lessons and some students

- 02:14 would understand while others had questions, but you could tell learning was happening.

- 02:20 Now imagine the same classroom, but when the teacher speaks, she uses a language

- 02:26 that students don't understand. As you can tell, it is impossible for children to learn this way.

- 02:33 Unfortunately, this problem is not uncommon. Nearly 37% of children are taught in a language

- 02:39 they don't understand in low and middle income countries. This is a major reason for the high

- 02:45 rates of learning poverty seen around the world. These children miss their chance to

- 02:50 learn foundational skills like reading that are critical for future success. Even worse.

- 02:56 These children tend to be the most vulnerable. This is because national policies often require

- 03:02 teachers to speak in a language. Students don't understand, but better policies are possible.

- 03:07 [Female voice]: There is a better way.

- 03:09 When children are taught in a language, they understand through basic spoke,

- 03:13 they have the opportunity to learn not only the language they speak at home, but also other

- 03:18 school subjects like math and science, as well as other languages. To end learning poverty issues of

- 03:25 language of instruction must be addressed. Let's give every child the chance to learn

- 03:31 let's ensure every child is taught in a language. They understand.

- 03:43 [Femi

- 03:44 Oke]: We are talking about the impact of using a

- 03:47 language of instruction and what that language of instruction should be to help children do better.

- 03:53 Hello, Alberto. Hello, Dina. Nice to see you. Two very important people from the World Bank. They're

- 03:58 going to tell you how important they are. Alberto introduce yourself to the world bank librarians.

- 04:02 [Alberto Rodriguez]: Well, it's great to be

- 04:06 here. Good morning. Good afternoon. My name is Alberto Rodriguez. I am the director of operations

- 04:11 and strategy for human development, and it's a great pleasure to join this conversation Femi.

- 04:16 [Femi Oke]: So good to have you. Hello, Dina.

- 04:18 Welcome to our conversation. Nice to see you, introduce yourself to our live audience today.

- 04:24 [Dena Ringold]:

- 04:25 Sure. Good morning Femi, and good afternoon to colleagues out there. And hi Alberto,

- 04:30 my name is Dina Ringgold and I'm regional director for human development in Western central Africa.

- 04:36 [Femi Oke]:

- 04:37 Let's start with you Alberto, just in case anybody's not aware of what learning

- 04:42 poverty actually means, would you just sum that up very quickly for us?

- 04:45 [Alberto Rodriguez]: Well, first of all, learning poverty

- 04:49 is a measurement that we're using in the bank to precisely identify the impact of low social

- 04:56 capacity, low economic capacity, and in general, social poverty on learning. And the fact that

- 05:02 actually learning is very inequitable. Our poorest and most vulnerable are actually the kids who are

- 05:10 learning the least. Now this is important because we are in a very particular context. I mean,

- 05:16 as you know well, we are in a moment where we have a crisis within a crisis, if you will,

- 05:24 we're going through this pandemic, and this pandemic has generated a terrible

- 05:28 crisis for families, students, educators. Before the COVID-19,

- 05:36 we already knew that we had a learning crisis. We already knew that not every

- 05:41 child was learning and that in fact, our poorest kids were learning the least those

- 05:45 that came from vulnerable families and countries have done a lot to bring children to school.

- 05:51 [Alberto Rodriguez]: But now they're starting to realize, and

- 05:53 they were starting to realize before the pandemic, that learning was very, very limited, even though

- 05:57 kids may have been in school. COVID has threatened things even further. The reality is that the twin

- 06:05 shock of school closures and the economy crisis, are really threatening to exacerbate this burning

- 06:12 crisis that we're talking about and that the learning poverty indicators are very clear about.

- 06:19 Now within this crisis, I think that this event is actually very, very timely because one can

- 06:25 not ignore the issue of language of instruction, as one of the important elements of this crisis,

- 06:33 language is essential to learning, instruction unfolds through language,

- 06:38 we all know that we all went to school and, and it is really ultimately very unfortunate that

- 06:45 millions of children, up to 37% of children in low and middle income countries are taught

- 06:52 in a language that they don't use at home and that they don't understand.

- 06:55 [Alberto Rodriguez]: So why are we surprised

- 06:57 that there is a learning crisis? Isn't it possible that in fact,

- 07:02 this is part a very important part of the issue of why children don't learn. It is true that teachers

- 07:08 need to be trained curriculums improved, and all of the educational inputs can help

- 07:14 improve learning. But language of instruction can be very much at the center of the learning crisis

- 07:21 and that's why this is important. And I would argue that that good language policies are still

- 07:29 an exception and not the rule. And this is when focusing on language is important, and this is

- 07:35 why this event is important. And we want to bring this issue to the forefront of our education work.

- 07:39 [Femi Oke]: Dina. We are going to be looking in more detail

- 07:44 at the World Bank policy paper on language of instruction and what it means for different

- 07:50 regions, what it means for governments and policy makers. But there's something that I noticed

- 07:55 cause I read the policy paper and there's a correlation between learning poverty and children,

- 08:05 language of instruction where they're being taught in a language that is not

- 08:08 the language that they grew up speaking at home. So there's a direct correlation, particularly

- 08:13 on the African continent, bearing in mind your job and your role right now at the World Bank.

- 08:20 Can you explain what those difficulties are between learning poverty? So children's'

- 08:24 ability to do basic mathematics and being able to read and being taught in a language that they

- 08:30 don't actually speak or understand. Why is that such a big challenge on the African continent?

- 08:36 [Dena Ringold]: Thanks, Femi. And I think that those are

- 08:39 really critical questions from the perspective of our work in Sub-Saharan Africa as whole in

- 08:46 Western central Africa, in particular education and addressing the types of issues around the

- 08:53 learning crisis that Alberto just mentioned are key. And in our strategic priorities,

- 08:58 human capital and education for country's future growth, productivity, development, for

- 09:07 individuals, for families is absolutely central. And I think what we see in this report is that we

- 09:13 cannot make progress on learning, on improving education outcomes without considering language

- 09:20 of instruction. So if I take the region where I work the learning situation is dire four out of

- 09:29 five. Children are in learning poverty. I think we have the highest level of out of school children

- 09:35 in the world. And it's also one of the most rich and diverse regions as far as language goes.

- 09:43 [Dena Ringold]: So we, I think there are five

- 09:46 official languages in the region, but the truth is there 940 languages that's Western central Africa.

- 09:54 I think if you take the continent as a whole it's 1500 languages and many of these languages cross

- 10:01 borders. So I think you can already start to imagine some of the challenges that emerge for,

- 10:08 for policymakers, but these are challenges we have to tackle because as the report says, children

- 10:14 will learn more if they're taught in their first language. So I think this means really thinking

- 10:20 about how to do this, how to train teachers, how to select which of these multiple languages

- 10:29 schools can usefully provide and how to think about adjusting, learning materials and textbooks.

- 10:37 So I think this report puts those issues on the table in a really useful way.

- 10:42 [Femi Oke]: Dina I'm going

- 10:43 to share this question with you from World Bank live. And the question is Nigeria has over 500

- 10:50 languages. So deal point is so many languages or in the continent of Africa, how should

- 10:56 schools operate when there's so many different languages are spoken? That is sort of like a 101

- 11:01 challenge. What have you seen working effectively?

- 11:05 [Dena Ringold]: So I think these are great questions.

- 11:09 And I think one of the things that the report does really well is look at how to think about

- 11:20 both starting, right? So the importance of the early years, and I think we've seen examples

- 11:27 from across the world where starting kids in pre-primary and early childhood in their

- 11:34 mother tongue is really effective and you can do this in community schools.

- 11:39 New Zealand did this by having grandmothers teach indigenous kids the Maori indigenous language,

- 11:46 but there's also economies of scale, right? So even if you have 500 languages,

- 11:51 you can look at this and see, how, which languages are spoken by a greater number of people in order

- 11:57 to adjust policies and textbooks to capture the most kids, but it is absolutely a challenge.

- 12:03 [Femi Oke]: Alberto the policy

- 12:07 paper and language of instruction also says, we are here as a resource. What can the World Bank

- 12:13 do to help you governments, policy makers? Can you emphasize that when people are watching this,

- 12:20 when people then looking at the executive summary of the policy paper, when they're thinking we can

- 12:28 do this. What is the World Bank offering? What is the support that we're able to give?

- 12:32 [Alberto Rodriguez]: Well, as I said earlier,

- 12:34 this is a very important issue for us. There's a number of things that we are doing and in fact,

- 12:42 this paper itself is one of them where we're bringing forward research,

- 12:45 country level research that tells us what works and what doesn't work. You know, one thing that

- 12:52 we found that I think is extremely interesting is that the best way for a student to learn a second

- 12:59 language is to have their mother language as a strong basis and a strong foundation.

- 13:04 In other words, it is very understandable for example, that a parent will want their child

- 13:08 to learn English because they see high value in the child learning English. However, we

- 13:14 now bring forward research that shows that it is not a choice between that and the mother tongue,

- 13:19 you can do both. And in fact, both build on each other for stronger outcomes for that child.

- 13:24 [Alberto Rodriguez]: So I think there's a technical

- 13:26 element that the bank brings forward of knowledge, of research, of information. But this issue is not

- 13:32 only technical, this issue is also requires a commitment of society. And the reason is because

- 13:39 this is an issue that can be quite personal and even political language is a tool that is used

- 13:44 to pursue different societal and personal goals. And therefore there needs to be a conversation,

- 13:50 an agreement, a commitment from the population and from our government around this issue.

- 13:56 So I've pointed out the two issues, commitment, discussion about it and second technical aspects,

- 14:03 knowledge in both the bank can be a strong player. We're able to convene different actors

- 14:08 of societies, we're present in the countries and can help that discussion and can bring to

- 14:14 that discussion the knowledge, the research, and the evidence that is required to have an informed

- 14:20 discussion around this issue, making a sound plan around language and instruction is a key portion

- 14:28 of implementing it and making it a success for the learning of all students. We can help on that.

- 14:36 [Femi Oke]: I like that you address the elephant in the room,

- 14:40 and that is the language of instruction. Isn't just about a school policy. Sometimes

- 14:48 it is political about the language that taught in a country. So this, this question for World

- 14:55 Bank live is a good one. This observation teachers want to teach in a language that

- 15:00 kids understand. Some governments don't and many parents and teachers see why it is better for the

- 15:06 students to use their home, their local language in school, but the government requires instruction

- 15:10 in the official language of the country. So then what do you do? It's a hot topic. Know it's a

- 15:18 difficult topic to address Alberto, how will you guide us in the rest of our conversation?

- 15:23 [Alberto Rodriguez]: I think it is a difficult topic, but I think we

- 15:26 have to go back to the basics if you will. I think everyone, local governments, national governments,

- 15:32 we all want students to succeed. Our objective or goal is for students to succeed in school,

- 15:39 to be happy , to be active citizens of the world, contributors, both on the economy,

- 15:46 but also on the societal aspects. And therefore we focus on that ultimate goal

- 15:51 and we say, that's what we all want. Then we go back to the evidence and we say, how can that be

- 15:57 done? And that's where we find that children are more likely to be successful in school.

- 16:02 [Alberto Rodriguez]: If they learn in their own language,

- 16:04 even though they can learn other languages as well. And that's what

- 16:07 I indicated that it's not an either or it's an and option. You can learn both. And in fact,

- 16:13 when you have strong support and basis in your mother tongue, it is easier and it is

- 16:20 more effective to learn a second language. So this is really a consensus building process

- 16:26 where you focus on the ultimate result, the ultimate goal, and you work through

- 16:31 the evidence to get there. I think it is possible and I think we can help in that process

- 16:36 [Femi Oke]: Alberto and Dina,

- 16:38 thank you so much for kicking off our conversation today. I've been talking about this World Bank

- 16:43 policy paper on language of instruction. The very first one ever the PDF is 104 pages long. One of

- 16:52 the people who's responsible for that PDF, not by himself because it's the work of an entire team

- 16:59 is Jaime , come in here and introduce yourself, tell everybody who you are and what you do.

- 17:04 [Jaime Saavedra]: Thank you very much

- 17:06 Femi. This is Jaime Saavedra, I'm the global director for education in the world bank.

- 17:10 [Femi Oke]: So nice to have you. It's a beautiful

- 17:15 policy paper. It's accessible,

- 17:18 104 pages long, but you are going to condense that into the next few minutes.

- 17:23 [Jaime Saavedra]: Thank you very much. Thank you very

- 17:25 much Femi. Let me do the more complicated thing here, which is sharing my screen. I will do well.

- 17:33 And let me see if I'm succeeding or not. Okay. Great. Excellent. So to a certain extent,

- 17:44 many people would say, why would we need a policy paper and a seminar something that's called,

- 17:51 let's teach children in a language that they use and understand,

- 17:54 right? It might sound to a large extent that will sound obvious, right?

- 17:59 Isn't that something that we should be doing right? Isn't it obvious that

- 18:05 countries should be doing that? And unfortunately, and as I was already mentioning, I mean, there

- 18:12 are technical issues, there are political issues why that is not happening , we do have a problem

- 18:23 about a third of gifts, right? Are being taught in a language that they don't understand.

- 18:29 [Jaime Saavedra]:

- 18:30 And many kids in the world are failing in terms of attaining the foundational skills that they

- 18:36 nearly not being, they need in school in order to continue in school as I begged to introduce

- 18:46 just before the pandemic, we launched this number and this concept of learning poverty,

- 18:52 and we said, what's the share of students or children in general? But then what's the share

- 18:56 of children who cannot read and understand a simple text page? If you think this well,

- 19:02 this percentage should be zero, right? All kids should be able to learn and to be able

- 19:07 to read and understand by age. Unfortunately, that number is 53%. That is an extremely high number,

- 19:14 but most of those kids are in school. Some of them are not, but most of them are in school,

- 19:19 are not learning the foundational skills. And actually this number varies a lot across regions.

- 19:25 [Jaime Saavedra]: So it is still a worrisome 21% in East Asia, 13%,

- 19:29 anything in Europe and Central Asia, but it's almost 90% in Sub-Saharan Africa and between

- 19:35 the fifties and the sixties in Latin America and Middle-East and North Africa and in South

- 19:40 Asia. So this is really a failure, right? So we were saying, look, we do have a crisis here,

- 19:48 but this will be represented was just before the pandemic,

- 19:55 right? And now as Dina and Alberto were mentioning the pandemic is threatening,

- 20:01 but to make things much worse, we have a gigantic two in shock, right? Our school closures

- 20:07 and a huge economic crisis, which is decreasing both the quantity and the quality of education.

- 20:12 The dropout rates, we already have evidence that are going up. Learning losses are mounting,

- 20:20 and maybe this 53% will be increasing according to our simulations after these alone lone closures.

- 20:29 [Jaime Saavedra]: And our initial estimations were that this 53%

- 20:34 might be going up to 63%. And unfortunately, even this might be an underestimation given

- 20:41 the extent of the school closures that we see throughout the world. And unfortunately

- 20:46 this is a very unequal impact because not all children have had as the same access

- 20:51 to remote learning throughout this month. This learning crisis is intrinsically

- 20:58 connected to language, right? The students, a student home language, which is called L1, right

- 21:07 in the jargon of your specialists, right? If that language is her initial endowment of knowledge and

- 21:14 is the basic, the basis for a good start of, of learning to read or a good start learning math,

- 21:21 or other subjects that we want them to master in school. And unfortunately there are many

- 21:28 conditions in many countries in which the conditions for learning like are challenging.

- 21:32 [Jaime Saavedra]: And in addition, language diversity, right,

- 21:35 makes the challenge even tougher. And what we find is that 37%, this is a very high number of kids

- 21:43 in low income countries are being taught in the language that they don't understand. And there is

- 21:49 a very high correlation between learning poverty at the regional level and precisely that share of

- 21:55 children who... [voices in the background]... if they could mute their mic, that would be great.

- 22:07 In particular, we see that in Sub-Saharan Africa,

- 22:10 Middle-East and North Africa, very high rates of learning poverty, very high rates

- 22:16 of teaching children, not being teachen in the right language. Interestingly, in Latin America,

- 22:20 we see a very small number of kids that are being taught in the wrong language,

- 22:24 but that number is because there are a few countries, large countries like Argentina or

- 22:30 Columbia in which this issue of language diversity is not a gigantic one, but I mean, overall,

- 22:36 we do see a large correlation between learning poverty and the challenge that we're faced.

- 22:41 [Jaime Saavedra]: If the child

- 22:43 is not taught the language they speak at home, they are more likely to beat from the bottom

- 22:48 40 of the socioeconomic scales. Right? If schools in that area are, do not have the right language,

- 22:55 they might just never enroll. And if they do, they might be absent from class,

- 22:59 they might drop out, they might never achieve the cognitive, academic and language skills.

- 23:02 [Jaime Saavedra]: They might drop out. They might never achieve the

- 23:02 cognitive academic language skills that we want them,

- 23:05 but there is a better way. And the better way is about a policy package.

- 23:10 And I emphasize the word package because we say we need to train teachers. We need books. We need

- 23:15 problem covered in the classroom. Yes, we need all things. But the key things that we need to

- 23:20 have a package of interventions, if we want to move the needle of learning. And the first

- 23:25 element of that package is what Alberto was saying is political commit. It's political

- 23:30 and technical commitment. And sometimes that political commitment is about the willingness to

- 23:36 measure learning even if that brings us bad news, to measure learning, set targets and move fast.

- 23:41 [Jaime Saavedra]: Second part of the package,

- 23:43 supporting teachers. Third part of the package, provide quality and age-appropriate books. Make

- 23:48 sure that all kids have books and texts in their hands. Fourth, teaching the right language,

- 23:54 right? And fifth, engage parents and the community because there

- 23:57 has to be a continuity of the learning process between the school and the home.

- 24:02 So we need to implement all this package including digital language of instruction.

- 24:07 [Jaime Saavedra]: And if that happens,

- 24:09 our research is showing that if the child is starting to write in the right language, learning

- 24:16 will be faster and will be more efficient. And actually as it was mentioned already,

- 24:23 the acquisition of the second language, right? What they call L2 would be even easier, right?

- 24:30 Students will develop more confidence and learn with more confidence, other academic subjects

- 24:35 and develop their good cognitive abilities. And what's more important, there will be a

- 24:39 better interaction between teachers and students, right? The school would be a nicer place for kids.

- 24:45 And the school would be a more inclusive, effective, and efficient place for learning.

- 24:50 [Jaime Saavedra]: Let me close with defining very quickly what are

- 24:54 those effective language of instruction policies, and let me summarize this in five principles.

- 25:00 The first one is teach children in the language they understand through the first

- 25:05 six years of primary school. The early grades are the most important one. The second one is teach in

- 25:12 that language, not only reading and writing, but other subjects as Math, Science, History. Third

- 25:19 principle, introduce the additional language with a focus of oral and language skills at the right

- 25:26 moment. Fourth principle, continue then working in both languages, right? In the second language

- 25:32 but also continue emphasizing instruction in the mother tongue. And fifth principle is we need to

- 25:41 plan well. We need to implement policies, evaluate them, monitor their working well and adjust.

- 25:48 [Jaime Saavedra]: This is a learning

- 25:49 process. And it's a very complex process. All this thing is easier said than done. This

- 25:54 is a very complex implementation challenge here. First of all, we need to do a very

- 26:00 careful language mapping. I mean, just understanding who speaks what and where,

- 26:05 it's not trivial at all. And you were mentioned the case of Nigeria which you have 500 languages,

- 26:10 but just understanding clearly what is being spoken in each community is a very complex issue.

- 26:18 [Jaime Saavedra]: Then you need to decide on teaching

- 26:20 and learning materials on which languages. It might be very difficult to do it in 500.

- 26:25 You need to choose what will be the 20 or 30. That was my case when I was ministering Peru.

- 26:30 We had to develop materials in 22 languages, which was a very tough challenge, right? But

- 26:36 you need to do that. And it was very happy of approving new alphabets in some cases,

- 26:40 right? That was fantastic, right? It's really making a change in the life of people.

- 26:44 [Jaime Saavedra]: Third, you need to recruit teachers, allocate

- 26:48 them in the right places. Ideally, teachers that will know both languages, which is not easy,

- 26:53 right? And you really need to support it. And we need to measure learning all the time to see if

- 26:58 things are happening. And obviously, technology in these day and ages can really help. And

- 27:06 public policy is not easy, right? We need to adapt policies to ensure that they also

- 27:11 meet the needs of children with disability and those living in fragile and conflict settings.

- 27:15 [Jaime Saavedra]: Let me finalize saying that yes,

- 27:19 this is difficult. This is tough public policy, but this is essential public policy. And there

- 27:24 has been some successes. In Cameroon, right? Kom was introduced as a language of instructions in

- 27:29 the first three grades and then transitioned to English in the fourth one. In Uganda,

- 27:34 12 local languages introducing the first three grade, then transition to English in grade four.

- 27:39 Peru is use a local languages in the early years, although not yet in the whole country.

- 27:43 And then Spanish becomes the language of instruction, depending at the moment in

- 27:47 which was the child's original Spanish fluency. We know these cases. There is evidence that

- 27:56 learning scores will improve in our and every program.

- 27:58 [Jaime Saavedra]: What's our commitment? It's a very

- 28:02 loud and clear commitment. We need to make sure that we will continue working with countries and

- 28:07 with governments to make sure that all children are taught in the language that they understand

- 28:12 if we want to give them the future they deserve. Thank you very much, ma'am. You're muted, Femi.

- 28:19 [Femi Oke]:

- 28:23 Thank you, honey. I have something I want to share with you, and this comes from World Bank live,

- 28:28 as you were speaking, as you were giving your presentation. This is Julia Roman Menacho,

- 28:35 "Very interesting topic but in Bolivia, the native indigenous children are taught in Spanish

- 28:41 even if they speak Aymara, Quechua, Guarani or other languages. This is

- 28:46 detrimental to the learning of boys and girls. This situation must be changed."

- 28:52 I mean, you did that in Peru. Can any of the neighboring countries also do that?

- 28:57 [Jaime Saavedra]: Look, yes they can, and they should

- 29:00 and it's happening. And we're going to hear about the case of Ecuador in a few minutes in which yes,

- 29:06 they are implemented those policies and it's difficult. I can understand that. It's difficult

- 29:10 sometimes from a political perspective because parents say, "No, I want the kids

- 29:15 to learn in Spanish." But as Eduardo Alberto was saying, right? Yes, this is correct. This

- 29:20 is a valid desire. We need to do that, but we will do it in a more effective way if we start

- 29:26 first in Quechua or in Aymara and then the children transits to Spanish. The challenge

- 29:32 is that we need to find teachers in all places that will master both languages. That will be

- 29:37 ideal. We need to develop the reading materials in both languages and that's difficult public policy,

- 29:44 but it's really doable and I think we're going to hear very good examples of this happening.

- 29:48 [Jaime Saavedra]: It happened in Peru and I would say for us,

- 29:52 the easy part what's complicated was a huge amount of work of many technical people of developing

- 29:58 materials. And in some cases regarding languages in the Amazon create new alphabets, right?

- 30:05 But that's the easy part in quotes, because then the training that's supportive of teachers,

- 30:10 that's the more complicated one, right? And we need to deploy all teachers across the whole

- 30:16 country. That's more complicated and that might take some time, but we need to do it.

- 30:21 [Femi Oke]: All right. We're about to

- 30:22 hear how complicated it is. Jaime will be back at the end of our program with his reflections of our

- 30:27 two round tables. We have two round tables. The first one will be looking at challenges, language

- 30:35 of instruction in place and how various different countries and regents are dealing with that

- 30:40 challenge. And the second round table will be looking at implementation. How to get this done?

- 30:46 [Femi Oke]: All right, round table number one,

- 30:48 our virtual round table. On it, we have Minister Stanislas Ouaro from Burkina

- 30:54 Faso. We have Vice Minister Cinthya Game from Ecuador. And Dr. Hanada Taha is also joining

- 31:04 us from Zayed University and also Adama Ouane, former director of UNESCO Lifelong Learning.

- 31:11 Nice to see all of you. I'm going to get you to do your own introduction so you can ground yourself

- 31:16 in why you're so important in this conversation. Now it is not going to be a Ted talk introduction,

- 31:20 because you're all brilliant people, but just a brief introduction so we understand

- 31:24 your connection with language of instruction and why you care about that so much. Minister

- 31:31 Ouaro from Burkina Faso, go ahead. Introduce yourself to our World Bank live audience.

- 31:35 [French interpreter]:

- 31:40 Okay. Thank you very much for putting together this meeting. Thank you for the initial

- 31:50 presentation and the importance of teaching in the mother tongue. I am the education minister.

- 31:59 And we call it the Ministry of National Education, Literacy and Promotion of National Languages,

- 32:10 which shows the will of the government to promote the national languages and the use

- 32:15 of these languages in education to promote, to value and to protect national languages,

- 32:24 preventing them from disappearing as it happens to other countries. So the first

- 32:30 difficulty that we face in Burkina Faso. It has to do with the number of languages.

- 32:32 [Femi Oke]: So minister, if

- 32:33 I may, I'm going to say hello to your other co-panelist and then we will come back to you.

- 32:42 [French interpreter]: [Speaking French]

- 32:43 [Femi Oke]: But I love

- 32:44 how enthusiastic you are to get to the challenges.

- 32:55 [French interpreter]: [Speaking French]

- 32:56 [Femi Oke]: I will come back to you.

- 32:56 [French interpreter]: [Speaking French]

- 32:56 [Femi Oke]: So we move on to the vice minister,

- 32:58 Cinthya Game for Ecuador. Vice minister, please introduce yourself and your connection

- 33:03 with why language of instruction is so important in your country.

- 33:09 [Cinthya Game Vargas]: Morning everybody. I'm Cinthya.

- 33:18 In Ecuador, the policy of intercultural bilingual is very important because I have 14 nationalities

- 33:29 and different cultures. And it is a challenger of Ecuador change this policy.

- 33:37 [Femi Oke]:

- 33:39 Thank you very much. We move on to Dr. Hanada Taha.

- 33:43 Nice to have you. Your connection with language of instruction, why it's so important in your work?

- 33:50 [Hanada Taha]: Hi Femi. Hi, everybody. Lovely to be here.

- 33:55 For us with the Arabic language and the Middle East and North Africa region,

- 34:00 because of the issue of diglossia which is a phenomenon happening with the Arabic language

- 34:05 where you'll have a standard form and then many dialects, this could cause a challenge

- 34:11 that we will need to smartly work around. We will get to discuss it eventually. Thank you.

- 34:16 [Femi Oke]: Looking forward to it. And Adama Ouane, thank you

- 34:19 for your patience. Your connection with language of instruction, why you care so much about it?

- 34:31 [Adama Ouane]: I have devoted my whole career to this issue of

- 34:39 language of instruction. I've been working for 40 years in education and also together with UNESCO

- 34:47 for life learning. This issue is basic essential and

- 34:54 I am very happy to see that the World Bank is talking about this issue today.

- 35:01 [Femi Oke]: Minister Ouaro, let's go back to you.

- 35:05 The benefits of teaching children in a language they understand in Burkina Faso, what are they?

- 35:15 [French interpreter]:

- 35:20 There are many advantages to that. The first one is that that shortens the time of instruction.

- 35:30 The primary school is six years in Burkina Faso normally, but when we teach these children in

- 35:38 French which is the official language and one at the same time, we can shorten the time that takes.

- 35:51 Too many mics are on at the same time.

- 35:57 [Femi Oke]: sylviam11@aol.com,

- 35:59 please mute yourself so that the minister can continue. Please mute this. Or it may well be

- 36:07 one of our interpreters. Minister, please continue. We still hear you.

- 36:15 [French interpreter]:

- 36:18 So this is the first advantage and benefits. We shorten the time

- 36:25 for instructing these children. And there are economic advantages, development advantage for

- 36:31 children and in Burkina Faso, there are many children who are not in school, who are out of

- 36:41 the education system. They don't go to school or they will never have access to education.

- 36:48 And with other countries in the region, like Mali, Niger, we have put together what we call

- 36:58 accelerate education strategy so those children go to school for a year and then allows them to make

- 37:09 up for the gap that they have one year, two years. So the first year of schooling covers nine months.

- 37:19 During the two first months, the instruction is given them in the mother tongue of the child.

- 37:26 And then second month, we start using French. And the third grade, in fourth grade, we continue

- 37:36 teaching other things. So it shows how important is to use the mother tongue at the beginning.

- 37:42 [French interpreter]: I am a teacher. I am also researcher,

- 37:46 a researcher at the university. It is important to learn other subjects like Math and others.

- 37:56 It depends on the basis that this is done. For instance, for French, we do that later

- 38:09 at the beginning. Later, in the process of education, we introduce other languages.

- 38:17 But if you shift from one language to another too often, then it will be harder for the children to

- 38:24 understand, to learn Maths and other subjects. But if you teach them in their mother tongue, this is

- 38:31 good because they learn better, they feel more motivated to go to school. Therefore,

- 38:40 there are many advantages and it's wonderful to see that World Bank is interested by that issue.

- 38:46 [Femi Oke]: Bless you, minister. Appreciate you. I want

- 38:49 to go to Cinthya, in Ecuador. So you explained what a big challenge you have, at least 14

- 38:55 different languages, multiple cultures. How are you ensuring that every child

- 39:01 learns to the best of their ability by cutting out that barrier between

- 39:07 a language that they may well be taught in school and the language that they grew up

- 39:10 learning at home. How are you doing that? That's one of the most popular questions that we're

- 39:15 getting on World Bank live right now. It's how do you do this? How do you do it in Ecuador?

- 39:19 [Cinthya Game Vargas]:

- 39:27 Oh, it's a question very important for here. Within this framework of action,

- 39:37 the Ministry of Education of Ecuador has been promoting a bilingual policy by

- 39:45 on the construction of an inclusive intercultural bilingual education system, that in addition to

- 39:53 focusing on the production of educational resources in the countries, 14 language,

- 40:01 by which it seeks to include the different cultural and ancestral knowledge for our peoples

- 40:09 within the teaching framework. We have worked on curricular contextualization

- 40:15 and in this framework, 14 different national curricula of intercultural bilingual basic

- 40:24 education have been designed. We have a secretary of the intercultural bilingual education system,

- 40:32 aiming and coordinating, managing, monitoring, and evaluating policy

- 40:39 in this area. And we seek to just concentrate this body to meet territorial needs.

- 40:46 We are all focused on research into life cycles of the various cultures intended to produce

- 40:53 educational material that allows for the understanding of the cultural roots of the nation,

- 40:59 with firming belief in importance of children and adolescence learning the language they master,

- 41:06 whether it is their mother tongue or another culturally close language.

- 41:12 [Cinthya Game Vargas]: We believe in language as a tool for

- 41:16 accessing knowledge. And that language is of paramount importance because it's facilitate the

- 41:24 relationship and position, theme of a subject in the social spectrum. In the third case,

- 41:31 as in the other, one of the results of linguistic direction will be the permanent reinvention of

- 41:40 cultural identities. And it is present still at this point where they turns plurinational and

- 41:49 inter-culturally acquired importance in all areas. One of them being in the educational sectors.

- 42:00 In Ecuador, the importance of children receiving their education in their language and cultural

- 42:07 environment has been understood. And this promise have been warranty of a constitutional right.

- 42:18 In 2016, Ecuador promote and let the negotiation of the general assembly

- 42:26 resolution to proclaim 2019 as International Year of Indigenous Language and subsequently

- 42:35 the proclamation of the indigenous language 2022-2032. This concentrates initiative of

- 42:46 great significance and immense symbolic value seeks to take action at the national

- 42:55 and international levels to recovers and revitalize indigenous language.

- 43:01 [Cinthya Game Vargas]: In this process, Ecuador has emphasizes the

- 43:05 importance of working for indigenous language in the educational sphere. Since it understand that

- 43:14 when a language disappears, what disappears are the people themselves, their knowledge,

- 43:22 their ways of life, their relationship with the land and their sense of community.

- 43:30 During the pandemic, as a result of collaborative work with UNICEF and Plan International,

- 43:40 educational guys we produce in the 14 ancestral language and currently

- 43:48 the minister of education is carrying out preliminary action such as the creation

- 43:55 of a registration platform for intercultural bilingual education units.

- 44:01 [Cinthya Game Vargas]: The launch of the I

- 44:03 Want To Be A Teacher contest for intercultural bilingual teachers

- 44:10 and permanence in the system and choose teaching in their language. Additionally, we are working

- 44:20 on researching the lifecycle of the people and nationalities to gather information on their

- 44:29 history for development of educational materials that allow bilingual teacher to have, at their

- 44:37 disposal. In this way, the different knowledge of the different cultures can be solved in a

- 44:44 mutually complementary manners. A strategic action of the minister in 2020 was the articulation with

- 44:54 the academic for the production of a bilingual intercultural education repository to offer the

- 45:03 public a bibliographic collection with material of bilingual intercultural education. Thank you.

- 45:11 [Femi Oke]: Thank you so much, Cinthya.

- 45:13 I want to go to the middle eastern north Africa region where Arabic has spoken widely at home

- 45:20 and widely at school. But it's not that simple. It's a little bit more complicated

- 45:26 than that. If you speak Arabic, you know why. Hanada, it's great to have you here.

- 45:32 You have been doing research into language of instruction long before

- 45:36 the World Bank put out their policy paper. So you are here to give us some tips and suggestions,

- 45:43 and also dig a little bit into the research that you've done. First of all, would you

- 45:46 explain that dilemma between Arabic spoken at home and then Arabic that is spoken at school?

- 45:51 [Hanada Taha]:

- 45:52 Thank you very much, Femi. This is a great question. So Arabic is a

- 45:57 diagnostic language. This means that there is a standard language that we all learn at.

- 45:59 [Hanada Taha]: That there is a standard language that we all

- 46:03 learn at school, but then at home we speak in the dialect of that country. Whether Lebanese,

- 46:10 Egyptian, Emirati, Saudi, whatever it is. Now these dialects, I have to say they are direct

- 46:17 derivatives of the standard form of the language. But with a lot of differences, be it phonological

- 46:30 sometimes semantics and tactic. So these differences make it a little bit difficult,

- 46:38 sometimes a lot difficult, depending on the dialect these kids come, from

- 46:42 when they go to school, having heard that specific dialect at home.

- 46:47 In school they are immediately thrown into the lap of, we call it modern standard Arabic,

- 46:53 which was the standardized form that all school materials is based on. And there is no bridging

- 47:03 stage or phase done for these kids, which really lead to many kids falling behind.

- 47:12 [Hanada Taha]: We can see it in the PIRLS and PISA results on

- 47:16 the reading measure that is done. We can see it in their schooling, on other things, even in TIMMS,

- 47:24 the math and the science tests that they do. So it is not just affecting the Arabic, but

- 47:31 it's affecting all learning that is happening in Arabic language. And it's really something that is

- 47:40 not spoken about much. It is something that is not discussed and just taken until recently, possibly,

- 47:48 taken for a fact that you will have a seamless transition from the home into the school. Knowing

- 47:56 that at home also what's happening nowadays, there is not that early exposure to modern

- 48:03 standard Arabic via let's say a TV that they watch cartoons, children's books that the parents read.

- 48:11 [Hanada Taha]: So all of this stuff,

- 48:13 when it's not happening and they are just immersed and a dialect that is quite different from the MSA

- 48:22 they are exposed to in school, it is really causing this tension,

- 48:26 a lot of tension educational and even at times it could be cultural, cognitive, it,

- 48:34 it could lead to kind of a resistance to learning modern standard Arabic about the relevance of it.

- 48:44 [Femi Oke]: We have so many

- 48:46 questions about this topic, they're all asking the same thing. What do you do about that?

- 48:52 Between standard Arabic and spoken dialect it can be so different from written standard language.

- 48:58 So then what do you do? What are you seeing happening in the Middle East and North Africa,

- 49:04 dealing with this break between a dialect spoken at home and the Arabic spoken at school?

- 49:10 [Hanada Taha]: Thank you. Lovely to speak about solutions

- 49:16 [crosstalk 00:49:14] for events. So there are many things be happening now.

- 49:19 So if you, a couple of weeks ago, probably the World Bank launched this wonderful policy paper

- 49:27 it was on advancing the teaching and learning of Arabic language with the

- 49:33 focus on how do you bridge this journey between the dialects and the modern standard Arabic.

- 49:40 [Hanada Taha]: Now within the various countries that

- 49:43 the discussion is starting to brew in a sense. I know Jordan has just launched a wonderful work

- 49:51 in research, which is something really important for this region, to base our decisions concerning

- 49:58 language of instruction on research, and they are researching the Glossier and the effect it has

- 50:04 on learning. And the solutions are honestly early exposure to modern standard Arabic via

- 50:12 children's books, via cartoons, via the talks, via listening to it, songs, rhymes, all of that stuff.

- 50:22 Making sure that when they enter school, there is actually a well fleshed out program that is

- 50:30 serving as a bridge between the dialects, the home dialects and the MSA curriculum, and ensuring that

- 50:38 the curriculum of the early years uses a lexicon that is very similar to the child's dialect.

- 50:47 [Hanada Taha]: It would be still standard form,

- 50:49 but it's the simplified standard form rather than using a very high language that would just

- 50:55 go beyond what the kids can do. So teacher training is another solution that people are

- 51:03 looking into now. Better teacher preparation in colleges and in universities, which has not

- 51:11 until today, it has not addressed this issue. So going into these different paths and steps will

- 51:21 be extremely helpful in redeeming this gap between the dialects and the modern standard Arabic.

- 51:26 [Femi Oke]: Thank you Hanada. You've been extremely

- 51:28 helpful to help us understand the challenges of language of instruction across the Middle east

- 51:33 and North Africa. Stay with us because I'm going to get all of our round tables speakers to come

- 51:39 back at the end of our program because I want to ask them for a single takeaway that they are going

- 51:44 to condense into a sentence. So they're going to be thinking about that sentence now, for now to

- 51:50 the end of the program. Let me bring in Adama. You may have heard earlier on in our program

- 51:57 that we've talked about the political nature of what the language of instruction is in schools,

- 52:04 but we didn't really, explicitly say why it was political and why

- 52:09 it's controversial. Adama you are so well versed on this topic. Can you break it down?

- 52:15 What would be political about the language that is the official language taught in schools? Why

- 52:21 is it problematic? And then how do you work around that Adama? Nice to see you go ahead.

- 52:31 [Adama Ouane]:

- 52:34 Thank you very much, Amy. Thank you to the World Bank

- 52:39 for this. Excellent. Excellent. It is, as we said, learning and education - [crosstalk 00:52:45].

- 52:48 [Femi Oke]: Adama. If I

- 52:52 may, can I ask you yet? Sit back. Fantastic. That is perfect. Yes. Yes. You have a fine face,

- 52:54 but we were seeing all of it (laughs). Okay. Please continue.

- 52:59 [Adama Ouane]: [Interpretation from French] So

- 53:07 I was saying that, of course not everything is language, but without language education

- 53:12 doesn't make any sense. It's really surprising if not really even disgusting to see that

- 53:22 in spite of all the experiments, all that was said in Britain, there's resistance to adoption. The

- 53:32 language of instruction. People say that there's no language politics, policy in the country.

- 53:40 Well, there are ideas and arguments on this, but at the same time, there's a lot of resistance

- 53:49 from parents, from technical financial partners, from teachers.

- 53:54 [Adama Ouane]: Very often, we talk about the scare crow

- 54:00 when there are so many different languages, the different sense that urban areas,

- 54:05 rural areas. And we talk about the technical aspects of language

- 54:12 as oral tradition. And we talk about the status of languages that are considered second class. And

- 54:22 the population, when they assume that they will be taught in their own language, I mean,

- 54:28 we need to have the materials for that. The costs of producing all that is enormous.

- 54:35 And there is also negative effect on the students. These opinions

- 54:52 are myths and these ideas, wrong ideas, don't resist the results of

- 55:00 research that has been developed for many years though.

- 55:03 [Adama Ouane]: We also need to admit that

- 55:07 languages are only equal before God and linguists, because there are languages that are more

- 55:13 prestigious that are more attractive, and that exists because of their presence in the world.

- 55:23 It's normal that the poor want to be taught or [inaudible] in those languages. So languages of

- 55:33 precision, but we thought for a long time that if you taught children in a language that's not

- 55:39 a very important language, we are wasting your time and we are wasting human capital.

- 55:45 [Adama Ouane]: But in reality, I must say we have asked parents,

- 55:52 "Do you want the happiness of your children or do you want them to learn in this language?"

- 55:56 But that's not the issue. The Document of the World Bank proves clearly that it's not a choice.

- 56:03 It's not a and or, or, but it's, and, and, and- the two issues. We're not trying to

- 56:13 exclude any languages, but we want to reinforce the first language, L1 is fundamental.

- 56:20 And then to learn an L2 or other languages for the needs of communicating with other people or

- 56:28 for work and to live. So the students must acquire their skills in the first language,

- 56:39 L1. It is a tremendous asset for their education, their social inclusion,

- 56:46 for their own autonomy and for the future of society altogether.

- 56:53 [Femi Oke]: Thank you so much. There are

- 56:59 teachers who are really concerned about knowing, they're watching World Bank live now,

- 57:04 they know that their students learn better in the mother tongue, but it's a challenge about how

- 57:12 to make that happen. What would you say to those parents, those teachers who already know what the

- 57:20 policy paper says because they're experiencing it. What would you say to encourage them?

- 57:25 [Adama Ouane]: Well, let me desk the switch in English quickly,

- 57:29 just to say, that in fact that the teachers are right to have concern about teaching in languages

- 57:38 which are not well equipped technically, which have gone to have a good tradition,

- 57:42 which they don't master themselves that often. And we know that this is possible. We have to go

- 57:50 beyond the language itself. Indeed, a package has been outlined right now, which are dealing with

- 57:57 the pedagogy- method of teaching and learning, the support, and also creating a whole ecology of

- 58:05 learning, which facilitate acquisition and further learning into this. So the question is really that

- 58:14 we can teach in any language provided that we have the right method, that we have the right material

- 58:22 and that also we give the right motivation provincial grant for acquiring basic knowledge.

- 58:29 [Femi Oke]: Mm (affirmative). I

- 58:31 have one more question. Thank you, Adama. I have one more question. I'm going to ask

- 58:37 Vista Cynthia, and also to Minister Rauru. And this one question is, but I just want a

- 58:43 very simple answer because it's a great question. And it really speaks to the heart of the matter.

- 58:49 Why are countries still teaching in the language of colonizers? Why is that happening?

- 58:57 I'm a little too enthusiastic about that question (laughs). Cynthia, I just want an immediate,

- 59:02 no filtered response to why it's 2021. Why are we still teaching you the language of

- 59:10 colonizers who were roaming around the world in the 18th and 19th centuries? Cynthia.

- 59:17 [Cinthya Game Vargas]: Or it's a question

- 59:22 is very important because Ecuador is colonized with Spanish and here live any nationalities and

- 59:36 use different language to work, two expressions and 14 language in this region and a different

- 59:48 region in 17 millions in our country. It's very difficult, but now I need to,

- 01:00:03 to live in this, different cultures is very important for Minister and President in Ecuador.

- 01:00:14 [Femi Oke]:

- 01:00:15 Thank you. Let me just bring in. I do notice the irony of, I am speaking in the language of

- 01:00:20 English (laughs), I hear the irony in everything I say. So-

- 01:00:26 [Cinthya Game Vargas]: And English is the second

- 01:00:28 language more in Ecuador, really a language and everybody learn English in the school and know,

- 01:00:43 learn this language of population as different culture [crosstalk] It's very important.

- 01:00:49 [Femi Oke]: Yeah. It's so important and I'm

- 01:00:51 so glad that this is now a trend. It's a movement that we are very aware of. Let me go back to the

- 01:00:55 minister who has this mission in the title of his job. It's in his job title, he's a teacher,

- 01:01:02 he's an educator. Minister, I'm going to ask you this very quickly. Why is Africa still teaching

- 01:01:11 many countries in the language of colonizers, and not in the language of the people who live there?

- 01:01:21 Go ahead. Very briefly though, Minister, because I have to move on to round table two.

- 01:01:24 [French interpreter]: [Interpretation from French]

- 01:01:31 It's due to the past, of course. Education has had the clear objective, which was to train people

- 01:01:45 in order to help the colonizers in what they were doing- translators. And then it went over to

- 01:01:54 education. But there is a basic difference among countries. In Ecuador, they speak 14 language. We

- 01:02:05 have 69 languages and dialects. And then we have the difference between dialects and languages.

- 01:02:16 And we can say, well we have more than 69 languages

- 01:02:21 [French interpreter]: And having to choose one language among 69

- 01:02:28 is going to create frustration and we have to take that into account also. We live in a globalized

- 01:02:37 world so you need to have a common language but we still are in favor of bilingualism,

- 01:02:46 but at the same time, those different languages have to be codified in order to be used today.

- 01:02:54 [Femi Oke]: Right.

- 01:02:55 [French interpreter]: 25 languages are being use in

- 01:02:57 a non-formal education. We have bilingual teaching, but there is still work to do.

- 01:03:05 We can all give up on French or English or Mandarin, or in favor of one

- 01:03:13 national language. We can all do that, but we have to teach and learn in those national languages,

- 01:03:22 but we need a language to be able to work in and to live in a globalized [crosstalk] world.

- 01:03:28 [Femi Oke]: All right, merci Minister.

- 01:03:30 Okay. So that was round table. Number one, for the challenges and how different countries,

- 01:03:37 different regions are approaching language of instruction for their young people.

- 01:03:41 Round table number two is going to be looking strictly at implementation. How do you get this

- 01:03:48 done? So, let me say hello to your panelists for round table number two.

- 01:03:54 We have a Minister grammar, Luca, we have professor Dina Campo, and we have Dia.

- 01:04:02 Nice to see all of you. I am going to get you to do your own introductions very briefly,

- 01:04:08 and then also connect yourself in your brief introduction to language of instruction,

- 01:04:12 why it is important to you, Minister Luca first of all. Nice to see you, please introduce yourself.

- 01:04:18 [Geremew Huluka]: Okay. Thank you. Geremew

- 01:04:23 Huluka, State Minister of Education in Ethiopia. So this issue is very

- 01:04:28 important in the Ethiopian context because it is one of the multilingual society. Thank you.

- 01:04:36 [Femi Oke]:

- 01:04:37 Professor Campo. Nice to see you introduce yourself.

- 01:04:40 [Dina Ocampo]: Thank you again. [foreign language]

- 01:04:47 Hello to everyone. I'm Dina Ocampo. I am a faculty member of the UV College of Education,

- 01:04:53 University of the Philippines. But before this, I worked for four years in the Department of

- 01:05:00 Education as vice minister for curriculum and instruction. And it was my job to

- 01:05:08 institutionalize mother tongue based, multilingual education in the Philippines.

- 01:05:14 [Femi Oke]: Nice to have you. Dhir, the reason why you're here

- 01:05:18 is in the title of your job title. So I'm going to get you to introduce yourself and then everybody

- 01:05:23 will go, "Ah, I know why he's in that round table panel." Go ahead, Dhir. Nice to see you.

- 01:05:28 [Dhir Jhingran]: Hello everyone. I'm Dhir Jhingran,

- 01:05:32 founder and director of the Language and Learning Foundation in India or LLF.

- 01:05:37 LLF was founded with the vision that all children will have strong, foundational skill in their

- 01:05:42 home and additional languages and develop to their full potential. So we are very closely linked with

- 01:05:49 today, evenings language of instruction agenda.

- 01:05:51 [Femi Oke]: All right,

- 01:05:52 great. Okay. Minister, let me start with you. Ethiopia has multiple languages, multiple ethnic

- 01:06:02 groups and so mother tongue instruction is incredibly important, very important.

- 01:06:08 How have you managed it in Ethiopia? What is the template that you can

- 01:06:12 share with other countries who also have multiple languages within their country?

- 01:06:26 Minister, do unmute yourself.

- 01:06:27 [Geremew Huluka]:

- 01:06:31 Sorry, sorry. Yeah. As you know, Ethiopia is the second most populous in Africa and

- 01:06:42 linguistically, as well as culturally it is the most diversified society. We do have more than 80

- 01:06:48 languages. Of course, before 1991, we do have only one language of instruction in Ethiopia.

- 01:06:57 So 1991 change of government from unitary to the federal system has brought opportunity

- 01:07:04 to use different languages as a medium of instruction in Ethiopia. Particularly the 1994

- 01:07:12 Ethiopian Education Training Policy, as well as the 1995 Constitution, as

- 01:07:20 given guarantee for the regions nations and the nationalities to decide their

- 01:07:26 language of instruction, as well as the official language by themselves.

- 01:07:30 [Geremew Huluka]: So this, this opportunity helped Ethiopia to have

- 01:07:37 different language of instructions. Like for example, currently we do have

- 01:07:43 30 languages in which we can teach different subjects and the 50 state languages, which we give

- 01:07:50 as a subject matter. And among this 17 of them are given from first grade to 12th grade. In

- 01:07:58 Ethiopian context, first grade means, age of seven and 12th grade means yeah, [inaudible].

- 01:08:06 [Geremew Huluka]:

- 01:08:09 We are successful in such ways, we are doing our best. We do have constituent back as well as

- 01:08:18 policy issue. Of course Ethiopia has endorsed it for the first time, the language policy of the

- 01:08:26 country. And we are revising our educational policy now. And we are seeing in that how to

- 01:08:34 manage these media of instruction, particularly for the motherland language or mother tongue.

- 01:08:42 [Femi Oke]:

- 01:08:44 Thank you for this. I'll come back to you. Let me just go to, Professor. You spearheaded

- 01:08:52 lots of efforts to get language of instruction, to match the language that children were learning

- 01:08:59 at home and could speak at home. Can you tell us about that? Because again, people want to know.

- 01:09:03 [Femi Oke]: This week at

- 01:09:03 home. Can you tell us about that? Because again, people want to know the how, how do you do this?

- 01:09:06 [Dina Ocampo]: I'll try to do it very quickly. The Philippines

- 01:09:10 has over 170 languages, and in this number of languages, we obviously there are languages that

- 01:09:20 are spoken by very many and languages that are spoken by very small numbers of people.

- 01:09:26 For example, certain indigenous groups would speak unique languages that only their group do use in

- 01:09:34 daily life. So there's a very large variance of numbers, of speakers and so on. It began

- 01:09:44 with many research over decades, and it was always a pendulum swinging between going to English,

- 01:09:52 and using Filipino even as our national language for learning. And then now at the moment we are at

- 01:10:00 multilingual education, we are using 19 languages of education from kindergarten to grade three

- 01:10:09 and many indigenous groups have made their own versions.

- 01:10:13 [Dina Ocampo]: We call this process contextualization Femi.

- 01:10:16 What we do, what the department has done is to create materials that are prototypes, which

- 01:10:24 then different groups or different language groups will now contextualize or localize into their own

- 01:10:31 languages, or better even is that they create their own. So one of the things that I can share

- 01:10:40 is that the implementation is very uneven. There is an effort. There's a huge effort,

- 01:10:48 and it's a continuing effort to improve the implementation and to improve the products

- 01:10:55 that are needed for children, to be able to learn for teachers, to be able to teach and all that,

- 01:11:00 but implementation in such a large country and with many diverse languages can be a challenge.

- 01:11:07 [Dina Ocampo]: Some of the things that had to be done were

- 01:11:12 mentioned in the report, actually, ours is a bit different. We don't deal with only two languages.

- 01:11:20 As I read the report, I noticed that the emphasis was really on a couple of languages,

- 01:11:25 but the Philippines situation is different. We have the local language or the mother tongue,

- 01:11:30 and then there is Filipino, and then there is English. And I was listening

- 01:11:35 to the conversation about why teach English at all, or which is one of the

- 01:11:41 language of one of our colonizer, because we had two or three.

- 01:11:44 [Femi Oke]: I saw you

- 01:11:45 laughing. When that question came up, I saw you chucking.

- 01:11:49 [Dina Ocampo]: And I was part of the research group that actually

- 01:11:54 asked parents and asked communities about that. And this is way back, like over a decade ago.

- 01:12:01 And I've been doing this for very long as well, just like Mr. Adama Ouane. And, we asked them

- 01:12:12 and they said that they were willing to learn, because language politics is also very

- 01:12:17 interesting, dominant languages, large groups of people speaking, also very established languages.

- 01:12:24 [Femi Oke]: And also what

- 01:12:25 might parents be keen to know, what might get my child ahead?

- 01:12:30 [Dina Ocampo]: Yes.

- 01:12:31 [Femi Oke]: If they speak a colonizer language,

- 01:12:35 are they going to do better? Are they going to do better in the world? I know that there are

- 01:12:39 situations in Nigeria where little kids growing up only speak English. They don't. And they're

- 01:12:47 in Nigeria and I'm so furious. I lost my mother tongue because my parents were immigrants and they

- 01:12:52 were scared to teach me Yoruba. They were scared that I would have an accent, which is not true,

- 01:12:59 we all us linguists know, that's not true. So this idea that, that language two,

- 01:13:06 that language two is going to get you ahead. That's very powerful, right, Professor.

- 01:13:09 [Dina Ocampo]: Yes, I call that

- 01:13:13 in one of the things I've written, the language of economic and social mobility,

- 01:13:19 but you know, there's another end to it, which I think is equally important is that

- 01:13:24 people love their language. Their languages. And so the notion of having only Filipino

- 01:13:32 as the Philippines language in schools was also not attractive to them. So, when the discussions

- 01:13:38 with parents went on, one of the things that came up was that if our language were taught in school,

- 01:13:47 which let's say Cebuano or Ilocano, one of the Philippine language is taught in school. And then

- 01:13:53 eventually the children learn also Filipino. And there's no way they're giving up English because

- 01:13:59 they want their children to do that. Then the policy has to listen to these aspirations as well.

- 01:14:07 And, that's the kind of complexity that we are dealing with in the Philippines.

- 01:14:13 [Dina Ocampo]: And I'm sure that many countries around this

- 01:14:16 table, they're dealing with that as well. So mapping that understanding

- 01:14:23 that children will learn better. Absolutely. If they learn in the language that they know

- 01:14:29 in their heart, in their minds, but also that parents have an aspiration that we must listen to.

- 01:14:37 And then there is an identity as a nation that was also important for policy makers.

- 01:14:46 With the work we had to try and work with teacher development,

- 01:14:52 we needed to work on instructional materials development, assessment was the killer,

- 01:14:59 assessment continues to be the most tricky part. I see Hanada nodding her head because that's

- 01:15:05 really where the most difficult part is. And that's still a work in progress where I'm from.

- 01:15:13 [Femi Oke]: Professor

- 01:15:14 [Dina Ocampo]: the lack of, of reading material. If I may, just

- 01:15:20 last point, the lack of reading material, we don't teach children to read for reading’ sake, right.

- 01:15:27 [Dina Ocampo]: We teach children to read, to make themselves

- 01:15:32 happy, for them, to love themselves, to love everything that comes with identity. But it

- 01:15:38 also means being able to relate to others, understand the lives of other communities.

- 01:15:45 And that comes through books for children who are far and of course, multimedia and so on. So,

- 01:15:52 not having sufficient reading material in an ambitious language program

- 01:15:59 will be one of the downfalls of such a program as well. So it's very important to prepare

- 01:16:06 those. And, I'm not talking about textbooks. I'm talking about happy books, trade books.

- 01:16:11 [Femi Oke]: Reading for fun, you know when

- 01:16:13 the kids sit in the corner and they're just lost in a book, what language is that book written in?

- 01:16:18 [Dina Ocampo]: That's why we're teaching them to read.

- 01:16:21 [Femi Oke]: Yeah,

- 01:16:22 professor, thank you. I love the way that you describe why we read. I sometimes forget that.

- 01:16:29 I think it's a utilitarian process and I forget how much as a little one. I

- 01:16:33 love reading. Oh my goodness. I said, thank you so much. You're not dismissed yet.

- 01:16:43 I'm going to come back to you, but just bring in Dhir because the language and learning foundation

- 01:16:49 has done a lot of work on this, and has evidence on

- 01:16:53 language one. That mother tongue instruction for young people. What can you share with us today?

- 01:16:58 [Dhir Jhingran]: Thank you, Femi. We work with in

- 01:17:02 collaboration with government state governments, because we want to bring about transformation at

- 01:17:07 scale in the teaching and learning process, get children's languages in the classroom.

- 01:17:12 We work on three major dimensions. When we work with state governments. The first is continuous

- 01:17:18 professional development. Within the government education systems, teachers, teacher educators,

- 01:17:23 master trainers, educational administrators. Helping create awareness, commitment, and capacity

- 01:17:31 to include children's languages and on multilingual education. Because the challenges

- 01:17:35 here are not about just knowledge and skills. These are beliefs and attitudes about non-dominant

- 01:17:41 languages, whether they should find place in the classroom, about purity of use of language,

- 01:17:46 about use of mixed language, et cetera. So what we do is we run blended courses of varying durations

- 01:17:55 in multiple modes, online, synchronous, asynchronous, pure learning interaction,

- 01:18:01 face-to-face workshops, sharing resources over WhatsApp, et cetera, handouts printed materials.

- 01:18:06 [Dhir Jhingran]: And our courses vary from about

- 01:18:09 just five hours to six weeks. And they're usually led by the government, an academic institution in

- 01:18:15 the government. So, that's our first pillar of work. The second is demonstration programs

- 01:18:21 to be creating a proof of concept that how L1 can be effectively used to improve learning

- 01:18:28 at school. And this is done in collaboration with governments, again in 50, 100, 200 or 500 schools.

- 01:18:35 The third pillar of our work is what we call system reform.

- 01:18:40 I have myself worked in the government for 25 years. So we don't actually go to

- 01:18:44 the government and say, we are here to reform you. We use our work of-

- 01:18:50 [Femi Oke]: That would not go down well, Dhir.

- 01:18:52 [Dhir Jhingran]: I know. So, what we do

- 01:18:54 is because of the professional development work and demonstration programs, we sort

- 01:18:59 of get an entry into things like pre-service teacher education. When teachers are recruited

- 01:19:06 to be able to bring in issues of linguistic diversity and multilingual education there.

- 01:19:12 How do you adjust learning outcome frameworks and assessments? Which was just mentioned

- 01:19:17 to ensure that children's languages are taken into account. And for example, language portals

- 01:19:23 in recruitment of teachers, so that teachers know children's languages. So these are approaches

- 01:19:29 to use these three pillars of work to try and bring about change at scale. Thank you.

- 01:19:34 [Femi Oke]: One of the things

- 01:19:35 that the professor mentioned Dhir, and I really like that, she was very honest, was talking about

- 01:19:41 the roadblocks to implementation, for instance, not having enough books. Once you start teaching

- 01:19:47 in language one in the mother tongue, but maybe you don't have enough material.

- 01:19:53 What are the challenges that you can see? What are they, because when you implement,

- 01:19:57 when you're doing implementation, you want to learn from other people's

- 01:20:01 mistakes. What are the mistakes that you've seen that you want to warn our viewers about?

- 01:20:07 [Dhir Jhingran]: Yeah,

- 01:20:10 I think children's materials are absolutely crucial, fun, interesting, simple materials. And,

- 01:20:17 that's crucial for learning as well. I think the mistake that many civil society organizations do

- 01:20:24 is to just make good materials. What's more important. And governments are looking for is,

- 01:20:32 are these materials linked to the curriculums, to the learning outcomes? And therefore it's

- 01:20:37 very important because we to introduce L1's students strong and home languages

- 01:20:42 formally in the classroom, is to be able to design materials that align with the curriculum

- 01:20:48 and learning outcomes. And to be able to show that this will result in improved learning.

- 01:20:53 [Femi Oke]:

- 01:20:54 I want to bring back the minister for education in Ethiopia. I have a question for you. It's such

- 01:21:00 a great question. A plus for this question on World Bank live, how does Ethiopia manage

- 01:21:06 national exams at the end of secondary school with so many languages being taught?

- 01:21:10 [Geremew Huluka]:

- 01:21:13 Oh, actually this country school is taught in English, by the way. It's not by, okay.

- 01:21:21 [Geremew Huluka]: [crosstalk]

- 01:21:22 [Femi Oke]: So all of

- 01:21:23 that wonderful implementation you were telling me about stops at what age? 10 11.

- 01:21:28 [Geremew Huluka]: Yeah. And some-

- 01:21:32 [Femi Oke]: And the thinking behind

- 01:21:32 that minister is what the, by that time you feel the kids are confident

- 01:21:36 in English, that they can then do their entire secondary school in English?

- 01:21:41 [Geremew Huluka]: Yeah. They learn all the subjects

- 01:21:45 in secondary school in English. They can learn their language as a subject. So then-

- 01:21:53 [Femi Oke]: This explains to me why I have so many

- 01:21:56 extraordinary conversations with Ethiopians, because they've had to learn English from

- 01:21:59 secondary school. They have to speak English from secondary school. Do you think that this may well

- 01:22:06 hinder the learning of secondary school students? If they have to learn in English?

- 01:22:12 [Geremew Huluka]: Yeah. The that's one of the challenges we have in

- 01:22:15 Ethiopia by the way. It was a debate. Some people argue that our students should have strong English

- 01:22:29 and others argue that no, they have to have knowledge in their mother tongue.

- 01:22:34 [Femi Oke]: Who's winning that argument minister?

- 01:22:37 [Geremew Huluka]: Yeah. Different individuals like

- 01:22:41 experts, actually. The government commitment is high in improving the mother tongue. And

- 01:22:49 also we are working on how to improve English it is maybe separate project. We are

- 01:22:56 planning to intervene, English communication in middle school, like seventh and eight grade.

- 01:23:01 [Femi Oke]: How powerful are you, minister?

- 01:23:03 Could you just say, let's teach secondary school in language one. Can you do that? No.

- 01:23:12 Professor on camera is like no, that's not going to happen. You're just making trouble moderator.

- 01:23:18 [Geremew Huluka]: No.